In the previous chapter, we defined discrete random variables and learned how to describe their behavior using Probability Mass Functions (PMFs), Cumulative Distribution Functions (CDFs), expected value, and variance. While we can define custom PMFs for any situation, several specific discrete distributions appear so frequently in practice that they have been studied extensively and given names.

These “common” distributions serve as powerful models for a wide variety of real-world processes. Understanding their properties and when to apply them is crucial for probabilistic modeling. In this chapter, we will explore nine fundamental discrete distributions: Bernoulli, Binomial, Geometric, Negative Binomial, Poisson, Hypergeometric, Discrete Uniform, Categorical, and Multinomial.

We’ll examine the scenarios each distribution models, their key characteristics (PMF, mean, variance), and how to work with them efficiently using Python’s scipy.stats library. This library provides tools to calculate probabilities (PMF, CDF), generate random samples, and more, significantly simplifying our practical work.

1. Bernoulli Distribution¶

The Bernoulli distribution models a single trial with two possible outcomes: “success” (1) or “failure” (0).

Concrete Example

Suppose you’re conducting a medical screening test for a disease in a high-risk population. Each test either shows positive or negative. From epidemiological data, you know that 30% of individuals in this population test positive.

We model this with a random variable :

if the test result is positive (success)

if the test result is negative (failure)

The probabilities are:

(we call this parameter )

(which equals )

The Bernoulli PMF

For any Bernoulli random variable with success probability , the PMF is:

This can also be written compactly as:

Expanding this for both cases to make it crystal clear:

When k = 1 (success):

When k = 0 (failure):

Let’s verify this works for our example where :

When : ✓

When : ✓

Key Characteristics

Scenarios: Coin flip (Heads/Tails), product inspection (Defective/Not Defective), medical test (Positive/Negative), free throw (Make/Miss)

Parameter: , the probability of success ()

Random Variable:

Mean:

Variance:

Standard Deviation:

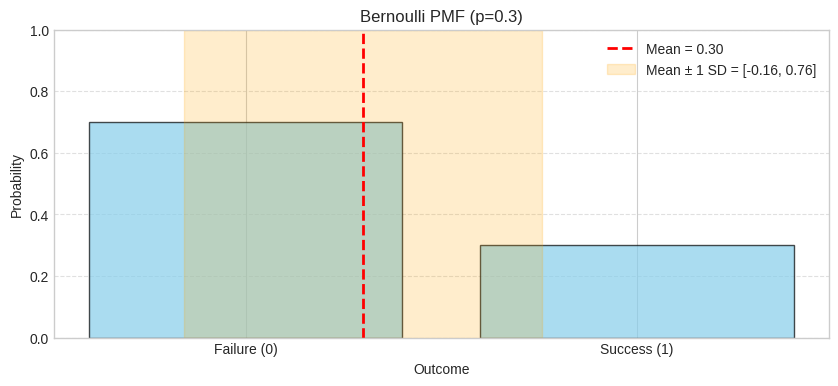

Visualizing the Distribution

Let’s visualize a Bernoulli distribution with (our medical test example from above):

The PMF shows two bars: P(X=0) = 0.7 for a negative test and P(X=1) = 0.3 for a positive test. The red dashed line marks the mean (), and the orange shaded region shows mean ± 1 standard deviation.

The CDF shows the step function: starts at 0 for x < 0, jumps to 0.7 at x=0 (the value when outcome is 0), stays flat at 0.7 until x=1, then jumps to 1.0 at x=1 (the value when including both outcomes 0 and 1). The red dashed line marks the mean.

Note: Here, P(X ≤ 0) = P(X = 0) = 0.7 because X can’t take negative values; in general, “X ≤ 0” means “at or below 0”, not “exactly 0”.

Reading the PMF

What it shows: The height of each bar represents the probability of that exact outcome

How to read: Look at the bar height to find P(X = k) for any specific value k

Practical use: Answer questions like “What’s the probability of success?” or “What’s the probability of exactly 1 positive test?”

Key property: All bar heights must sum to 1.0 (total probability)

Visualization aids: The red dashed line marks the mean (expected value), and the orange shaded region shows mean ± 1 standard deviation (where ~68% of values typically fall)

Reading the CDF

What it shows: The cumulative probability P(X ≤ k) up to and including each value k

How to read: The height at position k tells you the probability of getting k or fewer successes

Why step functions? For discrete distributions, probability accumulates in jumps at each possible value. Between possible values, the CDF stays constant (no additional probability)

Key identity: The jump at k equals P(X = k) — the size of each step up is the PMF value

Practical uses:

Find P(X ≤ k) directly by reading the height at k

Find P(X > k) by calculating 1 - P(X ≤ k)

Find P(a < X ≤ b) by calculating P(X ≤ b) - P(X ≤ a)

Key property: The CDF is right-continuous, always increases (or stays flat), and approaches 1.0

Visualization aids: The red dashed line marks the mean (expected value) as a reference point

Note on CDF visualization: The charts use where='post' in the step plot to create proper right-continuous step functions. This means the CDF jumps up at each value and includes that value in the cumulative probability.

Quick Check Questions

A quality control inspector checks a single product. It’s either defective or not defective. Is this scenario well-modeled by a Bernoulli distribution? Why or why not?

Answer

Yes - This scenario perfectly fits the Bernoulli distribution requirements:

Single trial: Checking one product

Two possible outcomes: Defective (success/1) or not defective (failure/0)

Fixed probability: The defect rate is constant for each product

If the defect rate is 5%, we’d use Bernoulli(p=0.05).

For a Bernoulli distribution with p = 0.3, what is P(X = 0)?

Answer

P(X = 0) = 1 - p = 0.7 - The probability of failure is 1 - p.

A basketball player has a 75% free throw success rate. If we model a single free throw as a Bernoulli trial, what are the mean and variance?

Answer

Mean = 0.75, Variance = 0.75 × 0.25 = 0.1875

Using the formulas E[X] = p and Var(X) = p(1-p):

E[X] = 0.75

Var(X) = 0.75 × (1 - 0.75) = 0.75 × 0.25 = 0.1875

You roll a six-sided die once. Is this well-modeled by a Bernoulli distribution?

Answer

No - A Bernoulli distribution requires exactly two possible outcomes. A die roll has 6 outcomes (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6), so Bernoulli doesn’t apply directly.

However, you could use Bernoulli if you redefined the experiment with a binary outcome:

“Does the die show a 6?” (Yes/No) → Bernoulli with p = 1/6

“Is the result even?” (Yes/No) → Bernoulli with p = 1/2

The key: Bernoulli requires exactly two outcomes.

True or False: A Bernoulli random variable can only take on the values 0 and 1.

Answer

True - By definition, a Bernoulli random variable X ∈ {0, 1}, where:

X = 1 represents “success” with probability p

X = 0 represents “failure” with probability 1-p

These are the only two possible outcomes.

2. Binomial Distribution¶

The Binomial distribution models the number of successes in a fixed number of independent Bernoulli trials, where each trial has the same probability of success.

Concrete Example

Suppose you flip a fair coin 10 times. Each flip is a Bernoulli trial with p = 0.5 (probability of heads). How many heads will you get?

We model this with a random variable :

= the number of heads in 10 flips

can take values 0, 1, 2, ..., 10

The probabilities are:

= probability of 0 heads (all tails)

= probability of exactly 5 heads

= probability of 10 heads (all heads)

The Binomial PMF

For independent trials with success probability :

for

where is the binomial coefficient (number of ways to choose successes from trials).

The Binomial PMF formula combines probability and counting:

Breaking down the formula:

: Probability of successes — each success is an independent Bernoulli trial with probability

: Probability of failures — each failure is an independent Bernoulli trial with probability

: Number of ways to arrange successes among trial positions

The probabilistic view (Bernoulli trials):

Any specific sequence of successes and failures has probability (by independence of trials). For example, the sequence “success, success, failure” has probability .

This shows why Binomial “counts successes in repeated Bernoulli trials”: it’s built from the ground up using the Bernoulli probability for each trial.

The combinatorial view (counting techniques):

The binomial coefficient is a combination that counts the number of ways to choose items from items when order doesn’t matter (see Chapter 3: Combinations).

In our context, it counts how many different sequences of trials yield exactly successes. For example, with trials and successes: represents the three sequences SSF, SFS, and FSS (where S=success, F=failure).

Why we multiply: Each of the sequences has the same probability . To get the total probability of exactly successes (in any order), we multiply the number of sequences by the probability of each sequence.

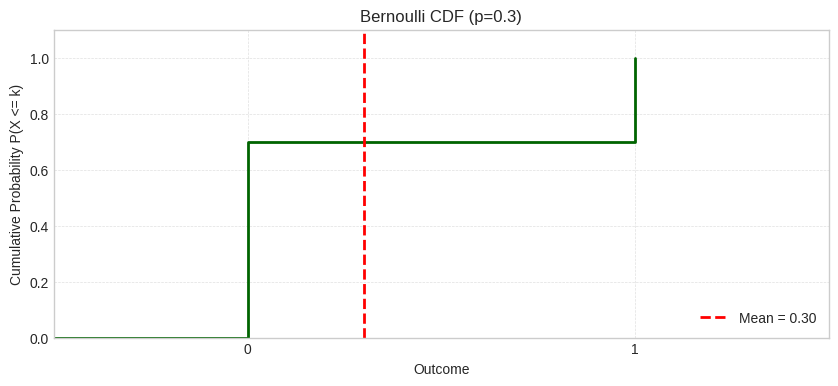

Visual example: Here’s how it works for trials, successes, with :

The diagram shows how the formula components work together: we count the sequences (3), calculate the probability of each sequence (0.144), and multiply to get the total probability of exactly 2 successes (0.432).

Let’s verify this works for our coin flip example (n=10, p=0.5):

Key Characteristics

Scenarios: Number of heads in coin flips, defective items in a batch, successful free throws, correct guesses on a test, customers who purchase

Parameters:

: number of independent trials

: probability of success on each trial ()

Random Variable:

Mean:

Variance:

Standard Deviation:

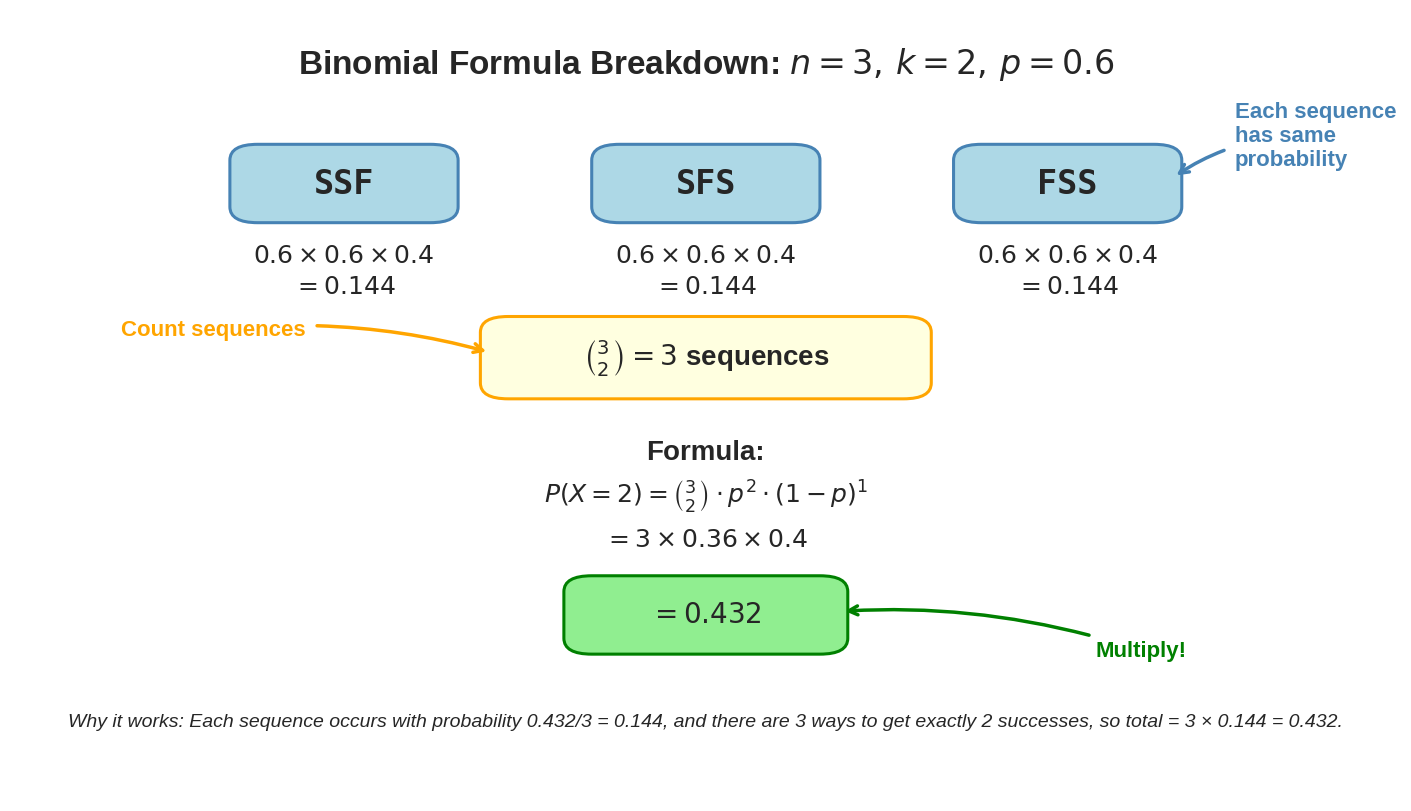

Visualizing the Distribution

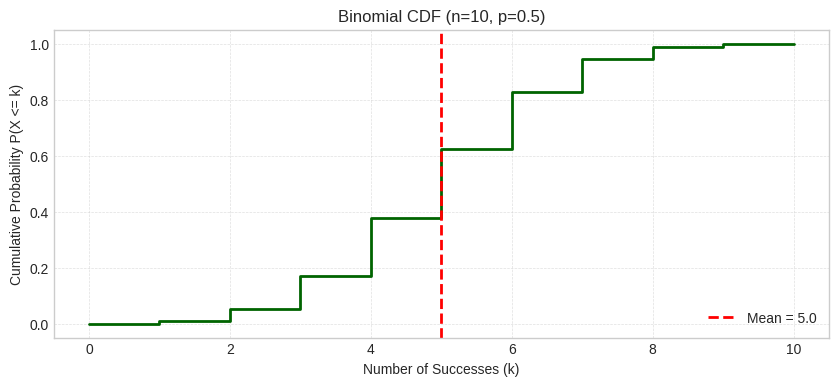

Let’s visualize a Binomial distribution with and (our coin flip example):

The PMF shows the probability distribution for the number of heads in 10 coin flips. The distribution is symmetric around the mean () since . The shaded region shows mean ± 1 standard deviation ().

The CDF shows P(X ≤ k), the cumulative probability of getting k or fewer heads. The red dashed line marks the mean.

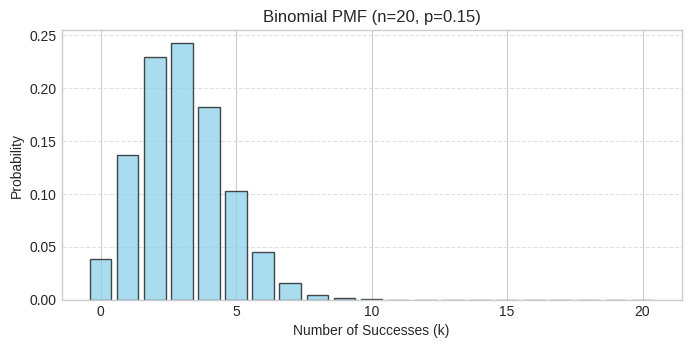

Modeling the number of successful sales calls out of 20, where each call has a 0.15 probability of success.

We’ll demonstrate how to use scipy.stats.binom to calculate probabilities, compute statistics, and generate random samples.

Setting up the distribution:

We create a binomial distribution object with our parameters (20 trials, 0.15 success probability):

import numpy as np

from scipy import stats

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Using scipy.stats.binom

n_calls = 20

p_success_call = 0.15

binomial_rv = stats.binom(n=n_calls, p=p_success_call)Calculating specific probabilities using the PMF:

What’s the probability of getting exactly 5 successful sales out of 20 calls?

# PMF: Probability of exactly k successes

k_successes = 5

print(f"P(X={k_successes} successes out of {n_calls}): {binomial_rv.pmf(k_successes):.4f}")P(X=5 successes out of 20): 0.1028

With a 10.23% probability, 5 successes is reasonably likely but not the most probable outcome (the mode is at 3 successes, matching the mean of np = 20 × 0.15 = 3).

Calculating cumulative probabilities using the CDF:

What’s the probability of getting 3 or fewer successes? Or more than 3?

# CDF: Probability of k or fewer successes

k_or_fewer = 3

print(f"P(X <= {k_or_fewer} successes out of {n_calls}): {binomial_rv.cdf(k_or_fewer):.4f}")

print(f"P(X > {k_or_fewer} successes out of {n_calls}): {1 - binomial_rv.cdf(k_or_fewer):.4f}")

print(f"P(X > {k_or_fewer} successes out of {n_calls}) (using sf): {binomial_rv.sf(k_or_fewer):.4f}")P(X <= 3 successes out of 20): 0.6477

P(X > 3 successes out of 20): 0.3523

P(X > 3 successes out of 20) (using sf): 0.3523

There’s a 64.85% chance of getting 3 or fewer successes, meaning there’s a 35.15% chance of getting more than 3 successes.

Note on Survival Function (sf): The sf() method computes the survival function, which is P(X > k) = 1 - P(X ≤ k). While mathematically equivalent to 1 - cdf(k), using sf(k) directly is preferable because it provides better numerical accuracy when dealing with very small or very large probabilities, and makes the code’s intent clearer.

Computing mean and variance:

Let’s verify the theoretical formulas E[X] = np and Var(X) = np(1-p):

# Mean and Variance

print(f"Mean (Expected number of successes): {binomial_rv.mean():.2f}")

print(f"Variance: {binomial_rv.var():.2f}")

print(f"Standard Deviation: {binomial_rv.std():.2f}")Mean (Expected number of successes): 3.00

Variance: 2.55

Standard Deviation: 1.60

As expected, we get a mean of 3.00 successes (20 × 0.15) with a standard deviation of about 1.6, indicating moderate variability around the mean.

Generating random samples:

We can simulate many rounds of 20 sales calls to see the distribution of outcomes:

# Generate random samples

n_simulations = 1000

samples = binomial_rv.rvs(size=n_simulations)

# print(f"\nSimulated number of successes in {n_calls} calls ({n_simulations} simulations): {samples[:20]}...") # Print first 20These samples represent 1000 different salespeople each making 20 calls, showing the natural variation in outcomes.

Visualizing the PMF:

Let’s see the complete probability distribution across all possible outcomes (0 to 20 successes):

# Plotting the PMF

k_values = np.arange(0, n_calls + 1)

pmf_values = binomial_rv.pmf(k_values)

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 3.5))

plt.bar(k_values, pmf_values, color='skyblue', edgecolor='black', alpha=0.7)

plt.title(f"Binomial PMF (n={n_calls}, p={p_success_call})")

plt.xlabel("Number of Successes (k)")

plt.ylabel("Probability")

plt.grid(axis='y', linestyle='--', alpha=0.6)

plt.show()

The PMF shows the probability distribution for the number of successful calls. With n = 20 and p = 0.15, the distribution is centered around np = 3 successes (the peak). The distribution is slightly right-skewed because p < 0.5. Notice that getting 0, 1, or 2 successes is quite likely, while getting more than 8 successes is very unlikely.

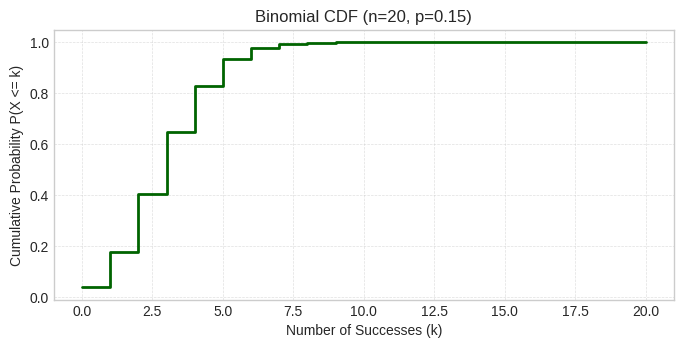

Visualizing the CDF:

The cumulative distribution shows how probability accumulates as we move from 0 to 20 successes:

# Plotting the CDF

cdf_values = binomial_rv.cdf(k_values)

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 3.5))

plt.step(k_values, cdf_values, where='post', color='darkgreen', linewidth=2)

plt.title(f"Binomial CDF (n={n_calls}, p={p_success_call})")

plt.xlabel("Number of Successes (k)")

plt.ylabel("Cumulative Probability P(X <= k)")

plt.grid(True, which='both', linestyle='--', linewidth=0.5, alpha=0.6)

plt.show()

The CDF shows P(X ≤ k), the cumulative probability of getting k or fewer successful calls. We can see that P(X ≤ 3) ≈ 0.65 (matching our earlier calculation), and by k = 8, we’ve accumulated nearly all the probability (close to 1.0).

Quick Check Questions

You roll a die 12 times and count how many times you get a 6. Is this a good fit for the Binomial distribution? Why or why not?

Answer

Yes, this is a good fit for Binomial. It satisfies all the requirements: (1) fixed number of trials (n = 12 rolls), (2) each trial is independent, (3) only two outcomes per trial (rolling a 6 vs not rolling a 6), and (4) constant success probability (p = 1/6 for each roll). The parameters would be n = 12 and p = 1/6.

For a Binomial distribution with n = 8 and p = 0.25, what is the expected value (mean)?

Answer

E[X] = np = 8 × 0.25 = 2 - The expected number of successes in 8 trials is 2.

A basketball player has a 70% free throw success rate. You watch her take 15 free throws. Does this scenario fit the Binomial distribution assumptions?

Answer

Yes, this fits the Binomial distribution with n = 15 and p = 0.7. Each free throw is independent, has two outcomes (make or miss), and the success probability remains constant at 0.7 for each attempt. We can use this to calculate probabilities like “What’s the chance she makes at least 12 out of 15?”

For a Binomial(n=20, p=0.3) distribution, what is the variance?

Answer

Var(X) = np(1-p) = 20 × 0.3 × 0.7 = 4.2

Using the variance formula for Binomial distributions.

True or False: In a Binomial distribution, each trial must have the same probability of success.

Answer

True - The Binomial distribution requires:

Fixed number of independent trials (n)

Each trial has only two outcomes (success/failure)

Constant success probability (p) across all trials

Trials are independent

If the success probability changes from trial to trial, Binomial doesn’t apply.

3. Geometric Distribution¶

The Geometric distribution models the number of independent Bernoulli trials needed to get the first success.

Concrete Example

You’re shooting free throws until you make your first basket. Each shot has a 0.4 probability of success. How many shots will it take to make your first basket?

We model this with a random variable :

= the trial number on which the first success occurs

can take values 1, 2, 3, ... (first shot, second shot, etc.)

The probabilities are:

= make it on first shot = 0.4

= miss first, make second =

= miss first two, make third =

The Geometric PMF

For trials with success probability :

for

This means failures followed by one success.

Let’s verify for our example (p=0.4):

✓

The formula has an intuitive structure:

: Probability of consecutive failures

: Probability of success on the -th trial

Multiply them: Since trials are independent, we multiply the probabilities

Example: For with :

First two trials must fail:

Third trial must succeed: 0.4

Combined:

This is why the formula captures “trials until first success” - it requires all previous trials to fail and the final trial to succeed.

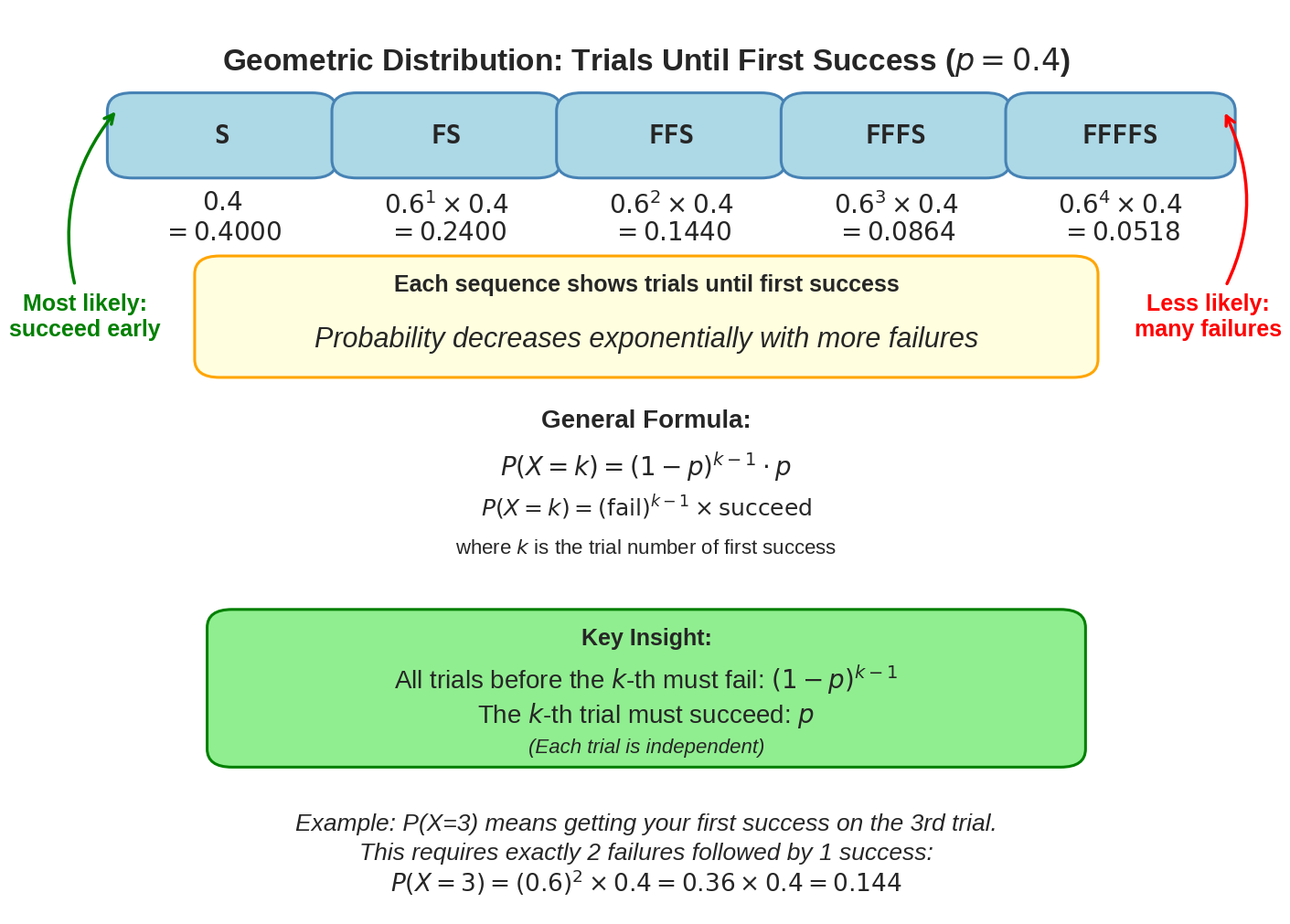

Visual example: Here’s how the geometric distribution works with (our free throw example):

The diagram shows how the geometric distribution works: each additional failure before success makes the outcome less likely. The probability decreases exponentially - notice how P(X=1) = 0.4000 is much larger than P(X=5) = 0.0518.

Key Characteristics

Scenarios: Coin flips until first Head, job applications until first offer, attempts to pass an exam, at-bats until first hit

Parameter: , probability of success on each trial ()

Random Variable:

Mean:

Variance:

Standard Deviation:

Relationship to Other Distributions: The Geometric distribution is built from independent Bernoulli trials and is a special case of the Negative Binomial distribution with (waiting for just one success instead of successes).

scipy.stats.geom uses the same “trial number” definition as we do, where represents the trial on which the first success occurs. The PMF is for .

Visualizing the Distribution

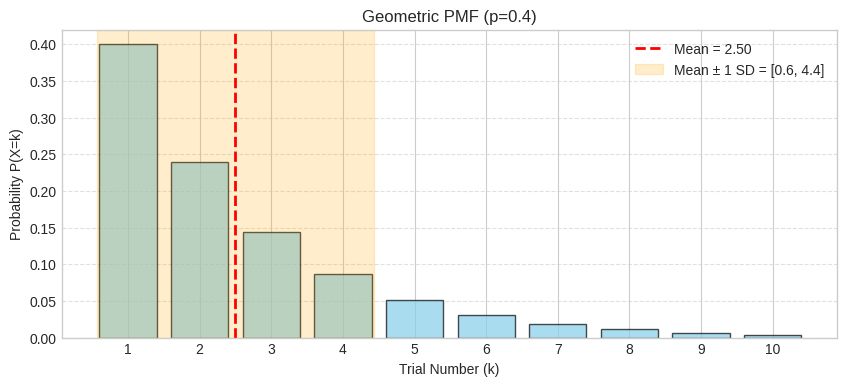

Let’s visualize a Geometric distribution with (our free throw example):

The PMF shows exponentially decreasing probabilities - you’re most likely to succeed on the first few trials. The shaded region shows mean ± 1 standard deviation.

The CDF shows P(X ≤ k), approaching 1 as k increases (eventually you’ll succeed). The red dashed line marks the mean.

Modeling the number of attempts needed to pass a certification exam where the pass probability is 0.6.

Let’s use scipy.stats.geom to explore probabilities and compute expected values. Remember that scipy’s definition counts failures before the first success, so we’ll translate between the two interpretations.

Setting up the distribution:

We create a geometric distribution with a success probability of 0.6 (60% pass rate):

import numpy as np

from scipy import stats

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Using scipy.stats.geom

p_pass = 0.6

geom_rv = stats.geom(p=p_pass)Calculating specific probabilities using the PMF:

What’s the probability of passing for the first time on the 3rd attempt? This means failing the first two attempts and passing on the third:

# PMF: Probability that the first success occurs on trial k (k=1, 2, ...)

k_trial = 3 # Third attempt

print(f"P(First pass on attempt {k_trial}): {geom_rv.pmf(k_trial):.4f}")P(First pass on attempt 3): 0.0960

There’s a 9.6% chance of passing on exactly the 3rd attempt. This is calculated as (1-0.6)² × 0.6 = 0.4² × 0.6 = 0.096.

Calculating cumulative probabilities using the CDF:

What’s the probability of passing within the first 2 attempts?

# CDF: Probability that the first success occurs on or before trial k

k_or_before = 2

print(f"P(First pass on or before attempt {k_or_before}): {geom_rv.cdf(k_or_before):.4f}")

print(f"P(First pass takes more than {k_or_before} attempts): {1 - geom_rv.cdf(k_or_before):.4f}")

print(f"P(First pass takes more than {k_or_before} attempts) (using sf): {geom_rv.sf(k_or_before):.4f}")P(First pass on or before attempt 2): 0.8400

P(First pass takes more than 2 attempts): 0.1600

P(First pass takes more than 2 attempts) (using sf): 0.1600

There’s an 84% chance of passing within 2 attempts, meaning only a 16% chance you’ll need more than 2 attempts.

Computing mean and variance:

Let’s find the expected number of attempts needed:

# Mean and Variance

mean_trials = geom_rv.mean()

var_trials = geom_rv.var()

print(f"Mean number of attempts until first pass: {mean_trials:.2f}")

print(f"Variance of number of attempts: {var_trials:.2f}")Mean number of attempts until first pass: 1.67

Variance of number of attempts: 1.11

On average, you expect to need 1.67 attempts (which matches the formula 1/p = 1/0.6). The relatively low variance suggests most people will pass within the first few attempts.

Generating random samples:

We can simulate many students taking the exam repeatedly until they pass:

# Generate random samples (trial numbers until first success)

n_simulations = 1000

samples_trials = geom_rv.rvs(size=n_simulations)

# print(f"\nSimulated number of attempts until first pass ({n_simulations} simulations): {samples_trials[:20]}...")These 1000 samples show the natural variation in how many attempts different students might need.

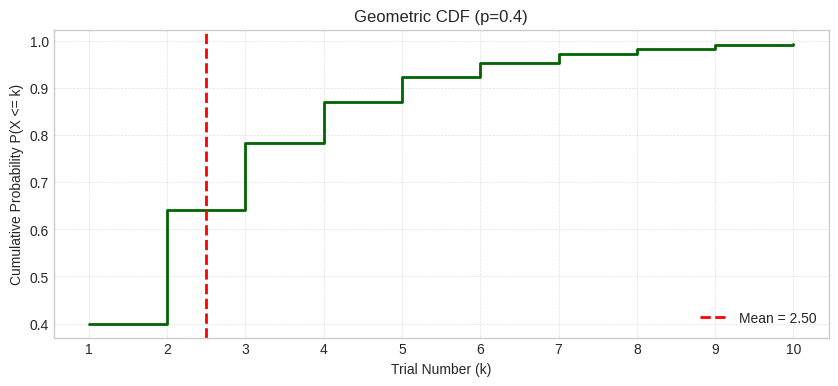

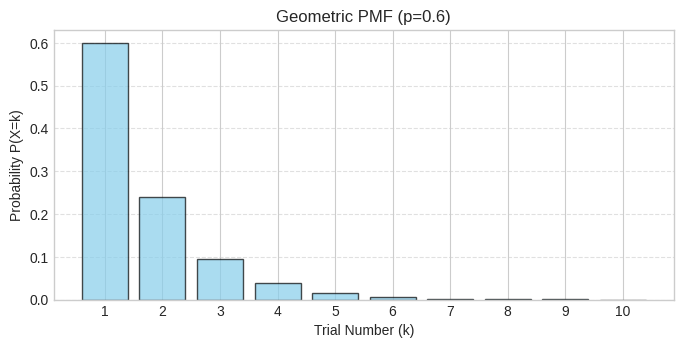

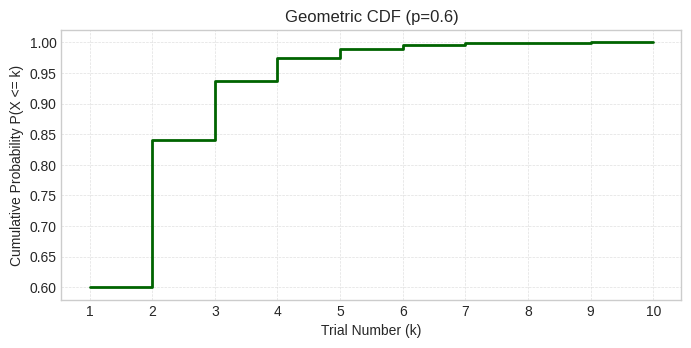

Visualizing the PMF:

Let’s visualize the probability of passing on each attempt number (showing the first 10 attempts):

# Plotting the PMF (using trial number k=1, 2, ...)

k_values_trials = np.arange(1, 11) # Plot first 10 trials

pmf_values = geom_rv.pmf(k_values_trials)

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 3.5))

plt.bar(k_values_trials, pmf_values, color='skyblue', edgecolor='black', alpha=0.7)

plt.title(f"Geometric PMF (p={p_pass})")

plt.xlabel("Trial Number (k)")

plt.ylabel("Probability P(X=k)")

plt.xticks(k_values_trials)

plt.grid(axis='y', linestyle='--', alpha=0.6)

plt.show()

The PMF shows exponentially decreasing probabilities - you’re most likely to pass on the first attempt (60%), then second attempt (24%), and so on. This characteristic “memoryless” exponential decay is unique to the geometric distribution. Notice how the bars get progressively smaller, with very low probabilities by attempt 5 or 6.

Visualizing the CDF:

The cumulative distribution shows the probability of passing by a given attempt:

# Plotting the CDF (using trial number k=1, 2, ...)

cdf_values = geom_rv.cdf(k_values_trials)

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 3.5))

plt.step(k_values_trials, cdf_values, where='post', color='darkgreen', linewidth=2)

plt.title(f"Geometric CDF (p={p_pass})")

plt.xlabel("Trial Number (k)")

plt.ylabel("Cumulative Probability P(X <= k)")

plt.xticks(k_values_trials)

plt.grid(True, which='both', linestyle='--', linewidth=0.5, alpha=0.6)

plt.show()

The CDF shows P(X ≤ k), rapidly approaching 1 as the attempt number increases. By attempt 2, there’s an 84% chance of having passed, and by attempt 5, it’s over 99%. This confirms that with p = 0.6, most people will pass within the first few attempts.

Quick Check Questions

You flip a coin until you get your first Heads. What distribution models this and what is the parameter?

Answer

Geometric distribution with p = 0.5 - Counting trials until first success, each trial has p = 0.5 success probability.

For a Geometric distribution with p = 0.25, what is the expected value (mean)?

Answer

E[X] = 1/p = 1/0.25 = 4 - Expected number of trials until first success.

You’re calling customer service and have a 20% chance each attempt of getting through. Should you model this with Geometric or Binomial?

Answer

Geometric distribution - You’re waiting for the first success (getting through), not counting successes in a fixed number of tries. Geometric models “how many attempts until success” with p = 0.20.

Binomial would apply if you made a fixed number of calls and counted how many got through.

Which is more likely for a Geometric distribution with p = 0.5: success on the 1st trial or success on the 3rd trial?

Answer

1st trial is more likely - The Geometric PMF decreases exponentially with k, so P(X=1) > P(X=3).

Specifically: P(X=1) = 0.5, while P(X=3) = (0.5)³ = 0.125

For a Geometric distribution, why does the variance equal (1-p)/p²?

Answer

The variance formula Var(X) = (1-p)/p² reflects the increasing uncertainty as p decreases:

When p is high (easy to succeed): variance is low (more predictable)

When p is low (hard to succeed): variance is high (could take many tries or get lucky early)

For example:

p = 0.5: Var(X) = 0.5/0.25 = 2

p = 0.1: Var(X) = 0.9/0.01 = 90 (much more variable!)

4. Negative Binomial Distribution¶

The Negative Binomial distribution models the number of independent Bernoulli trials needed to achieve a fixed number of successes (). It generalizes the Geometric distribution (where ).

The name comes from a mathematical connection to the binomial theorem with negative exponents, not because anything is negative! A more intuitive name might be “inverse binomial”:

Binomial: Fix number of trials → count successes

Negative Binomial: Fix number of successes → count trials

Think of it as the binomial distribution “in reverse.”

Concrete Example

You’re rolling a die until you get 3 sixes. Each roll has p = 1/6 probability of rolling a six. How many rolls will it take to get your 3rd six?

We model this with a random variable :

= the trial number on which the 3rd six appears

can take values 3, 4, 5, ... (minimum 3 rolls, could be more)

The probabilities are:

= all three rolls are sixes

= 2 sixes in first 3 rolls, then a six on 4th roll

And so on...

The Negative Binomial PMF

For trials with success probability and target successes:

for

Understanding the formula: This means successes in the first trials, and the -th trial is the -th success.

Think of r as “required” or “repeat” - the fixed target number of successes you need.

Think of k as “it took this many trials” - the variable total number of trials.

In our die example:

r = 3 (we require 3 sixes - this is fixed)

k = ? (it could take k = 3, 4, 5, ... trials - this varies)

Key: r is fixed, k is random

To build intuition, let’s see how the formula breaks down into three parts:

: Choose which of the first trials are successes (the -th trial must be a success, so we only choose positions for successes)

: Probability of successes

: Probability of failures

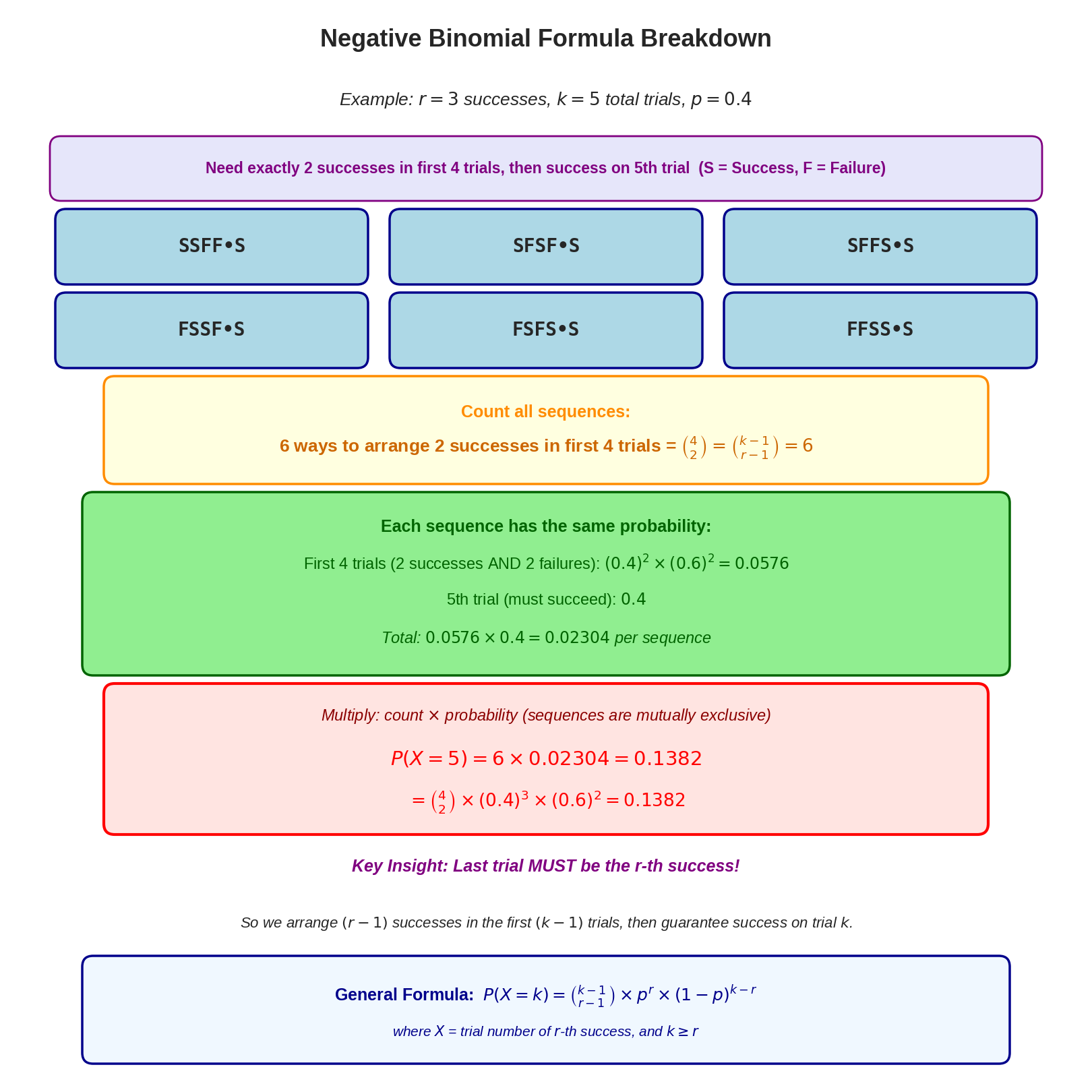

Intuitive example: For successes in trials with :

Need exactly 2 successes in first 4 trials: ways (e.g., SSFF, SFSF, SFFS, FSSF, FSFS, FFSS)

Each arrangement has probability for the first 4 trials

5th trial must succeed: 0.4

Combined:

This demonstrates how the formula combines all three parts.

The binomial coefficient ensures we count all possible arrangements where the -th success occurs exactly on trial . (We’ll see this visually in the diagram below.)

Now let’s mechanically apply the formula to our die example with different parameters: For (the probability it takes exactly 4 rolls to get the 3rd six) with sixes and :

Substituting , , into the formula:

Visual breakdown: The following diagram shows how the negative binomial formula counts all possible sequences and combines their probabilities:

The diagram shows how the negative binomial formula works: we need exactly successes in the first trials (which can be arranged in ways), and then the -th trial must be a success. Each of the 6 sequences shown has the same probability, and we multiply by the number of sequences to get the total probability.

Now that we understand the formula and its visualization, let’s summarize the essential properties of the negative binomial distribution:

Key Characteristics

Scenarios: Coin flips until getting r Heads, products inspected to find r defects, interviews until making r hires

Parameters:

: target number of successes ()

: probability of success on each trial ()

Random Variable:

Mean:

Variance:

Standard Deviation:

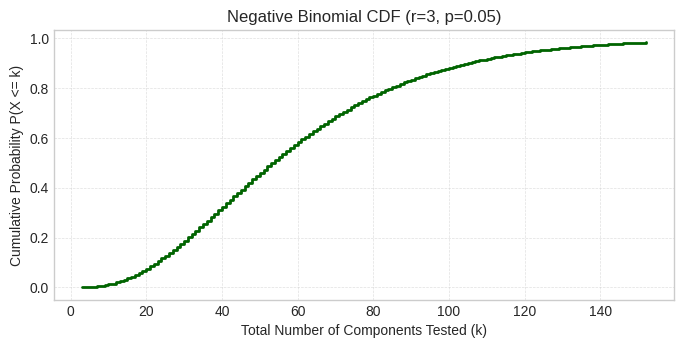

Visualizing the Distribution

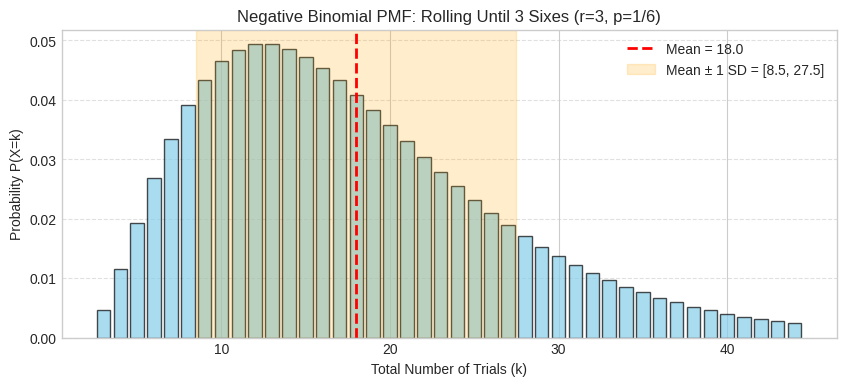

Let’s visualize our die example: Negative Binomial distribution with sixes and :

scipy.stats.nbinom counts the number of failures before the -th success, not total trials. We’ll use scipy’s definition in code but state results in terms of total trials.

The PMF shows the distribution is centered around the expected value r/p = 3/(1/6) = 18 trials. You can see our calculated P(X=4) ≈ 0.0116 as a small bar near the left tail at k=4. The shaded region shows mean ± 1 standard deviation.

The CDF shows P(X ≤ k), the cumulative probability of getting 3 sixes within k rolls. At k=4, the CDF shows P(X ≤ 4) = P(X=3) + P(X=4) ≈ 0.0046 + 0.0116 ≈ 0.0162, which is the very low cumulative probability in the left tail. The red dashed line marks the mean (18 trials).

A quality control inspector tests electronic components until finding 3 defective ones. The defect rate is p = 0.05.

We’ll use scipy.stats.nbinom to calculate the probability of needing a certain number of trials and compute expected values, keeping in mind scipy’s definition of counting failures.

Setting up the distribution:

First, we create the negative binomial distribution object with our parameters:

import numpy as np

from scipy import stats

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Using scipy.stats.nbinom

r_defective = 3

p_defective = 0.05

nbinom_rv = stats.nbinom(n=r_defective, p=p_defective)Calculating specific probabilities using the PMF:

What’s the probability we need to test exactly 80 components to find 3 defective ones? Remember that scipy counts failures (good components), so we need to convert:

# PMF: Probability of needing k components tested to find r defective

k_components = 80

num_good = k_components - r_defective

if num_good >= 0:

prob_k_components = nbinom_rv.pmf(num_good)

print(f"P(Need exactly {k_components} components to find {r_defective} defective): {prob_k_components:.4f}")

else:

print(f"Cannot find {r_defective} defective in fewer than {r_defective} components.")P(Need exactly 80 components to find 3 defective): 0.0074

This probability is quite low (0.0074 or 0.74%) because 80 components is far from the expected value.

Calculating cumulative probabilities using the CDF:

What if we want to know the probability of finding 3 defective components within 100 tests?

# CDF: Probability of needing k or fewer components

k_or_fewer_components = 100

num_good_max = k_or_fewer_components - r_defective

if num_good_max >= 0:

prob_k_or_fewer = nbinom_rv.cdf(num_good_max)

print(f"P(Need {k_or_fewer_components} or fewer components to find {r_defective} defective): {prob_k_or_fewer:.4f}")

else:

print(f"Cannot find {r_defective} defective in fewer than {r_defective} components.")P(Need 100 or fewer components to find 3 defective): 0.8817

There’s an 88.17% chance we’ll find all 3 defective components within the first 100 tests. This makes sense because 100 is well above the expected value (as we’ll see below).

Understanding scipy’s parameterization:

Scipy’s nbinom counts the number of non-defective (good) components before finding r defective ones. This is subtly different from counting total components tested:

# Mean and Variance (scipy's definition: number of non-defective items)

mean_good_scipy = nbinom_rv.mean()

var_good_scipy = nbinom_rv.var()

print(f"Mean number of good components before {r_defective} defective (scipy): {mean_good_scipy:.2f}")

print(f"Variance of good components before {r_defective} defective (scipy): {var_good_scipy:.2f}")Mean number of good components before 3 defective (scipy): 57.00

Variance of good components before 3 defective (scipy): 1140.00

Scipy tells us we expect to see 57 good components before finding 3 defective ones.

Converting to total components (our interpretation):

For practical purposes, we often care about the total number of components we need to test (good + defective). We can calculate this directly using our formulas and :

# Mean and Variance (our definition: total components tested)

mean_components = r_defective / p_defective

var_components = r_defective * (1 - p_defective) / p_defective**2

print(f"Mean number of components to test for {r_defective} defective: {mean_components:.2f}")

print(f"Variance of number of components: {var_components:.2f}")Mean number of components to test for 3 defective: 60.00

Variance of number of components: 1140.00

On average, we expect to test 60 components total to find 3 defective ones (57 good + 3 defective). Note that the variance is the same (1140) in both parameterizations—we’re just shifting the distribution by adding the constant r = 3.

Generating random samples:

We can simulate the inspection process by generating random samples. Each sample represents one complete “run” of testing components until we find 3 defective ones:

# Generate random samples (number of good components before r defective)

n_simulations = 1000

samples_good_nb = nbinom_rv.rvs(size=n_simulations)

# Convert to total components tested (good + r defective)

samples_components_nb = samples_good_nb + r_defective

# print(f"\nSimulated components tested to find {r_defective} defective ({n_simulations} sims): {samples_components_nb[:20]}...")These samples could be used for Monte Carlo simulation or to verify our theoretical calculations.

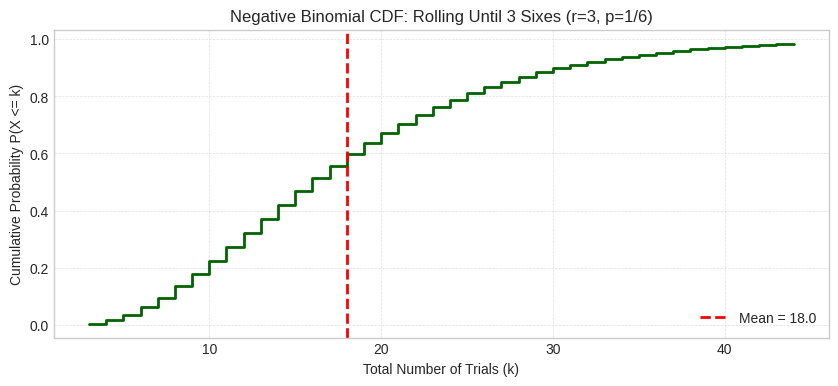

Visualizing the PMF:

Let’s visualize the full probability distribution to see the range of likely outcomes:

# Plotting the PMF (using total components tested k = r, r+1, ...)

k_values_components = np.arange(r_defective, r_defective + 150) # Plot a range

pmf_values_nb = nbinom_rv.pmf(k_values_components - r_defective) # Adjust k for scipy

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 3.5))

plt.bar(k_values_components, pmf_values_nb, color='skyblue', edgecolor='black', alpha=0.7)

plt.title(f"Negative Binomial PMF (r={r_defective}, p={p_defective})")

plt.xlabel("Total Number of Components Tested (k)")

plt.ylabel("Probability P(X=k)")

plt.grid(axis='y', linestyle='--', alpha=0.6)

plt.show()

The PMF shows the distribution centered around r/p = 60 components with considerable variability. The distribution is right-skewed, meaning there’s a long tail of possibilities where we might need many more components than average. Notice how the probability at k=80 (which we calculated earlier as 0.0074) appears as a small bar in the right tail.

Visualizing the CDF:

The cumulative distribution function helps us answer questions like “What’s the probability we’ll be done within k tests?”

# Plotting the CDF (using total components tested k = r, r+1, ...)

cdf_values_nb = nbinom_rv.cdf(k_values_components - r_defective) # Adjust k for scipy

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 3.5))

plt.step(k_values_components, cdf_values_nb, where='post', color='darkgreen', linewidth=2)

plt.title(f"Negative Binomial CDF (r={r_defective}, p={p_defective})")

plt.xlabel("Total Number of Components Tested (k)")

plt.ylabel("Cumulative Probability P(X <= k)")

plt.grid(True, which='both', linestyle='--', linewidth=0.5, alpha=0.6)

plt.show()

The CDF shows P(X ≤ k), the cumulative probability of finding 3 defective items within k tests. The S-curve shape is characteristic of CDFs. We can see that by k=100 tests, the CDF reaches approximately 0.88 (matching our earlier calculation of 88.17%). The CDF crosses 0.5 around k=53, meaning there’s a 50% chance we’ll need 53 or fewer tests to find all 3 defective components.

Quick Check Questions

You flip a fair coin until you get 5 Heads. What distribution models this and what are the parameters?

Answer

Negative Binomial with r = 5, p = 0.5 - Counting trials until getting r successes, each trial has p = 0.5.

For a Negative Binomial distribution with r = 4 and p = 0.5, what is the expected value (mean)?

Answer

E[X] = r/p = 4/0.5 = 8 - Expected number of trials to get 4 successes.

A basketball player practices free throws until making 10 successful shots. Each shot has a 70% success rate. Which distribution and why?

Answer

Negative Binomial with r = 10, p = 0.7 - We’re waiting for a fixed number of successes (r = 10), not just the first success. Each trial (shot) is independent with constant probability p = 0.7.

This is NOT Geometric because we need 10 successes, not just 1.

How is Negative Binomial related to Geometric distribution?

Answer

Geometric is a special case where r = 1 - Negative Binomial with r=1 is identical to Geometric.

Geometric: waiting for 1st success

Negative Binomial: waiting for r-th success (r ≥ 1)

For Negative Binomial, why is the variance r(1-p)/p²?

Answer

The variance r(1-p)/p² grows with both r and uncertainty:

Increases with r: Waiting for more successes means more trials and more variability

Increases as p decreases: Lower success probability means higher uncertainty in when you’ll reach r successes

For example:

r=1, p=0.5: Var = 1×0.5/0.25 = 2

r=5, p=0.5: Var = 5×0.5/0.25 = 10 (more variable with more successes needed)

r=5, p=0.2: Var = 5×0.8/0.04 = 100 (much more variable with low p!)

5. Poisson Distribution¶

The Poisson distribution models the number of events occurring in a fixed interval of time or space when events happen independently at a constant average rate.

Concrete Example

You receive an average of 4 customer calls per hour. How many calls will you get in the next hour?

We model this with a random variable :

= the number of calls in one hour

can take values 0, 1, 2, 3, ... (any non-negative integer)

The average rate is calls/hour.

The Poisson PMF

For events occurring at average rate :

where is Euler’s number.

Let’s verify for our example (λ=4):

✓

The Poisson formula emerges from the mathematics of rare events:

: Represents the “raw” likelihood of events based on the rate

: A normalization factor that ensures all probabilities sum to 1

Intuition: The Poisson distribution arises as the limit of the Binomial distribution when:

You divide a time interval into many tiny sub-intervals ( very large)

The probability of an event in each sub-interval is very small ( very small)

The average rate stays constant

For example, “4 calls per hour” could be modeled as 3600 one-second intervals where each second has probability of receiving a call.

Why mean = variance = λ? This unique property reflects the “memoryless” nature of the Poisson process - events occur randomly and independently at a constant average rate.

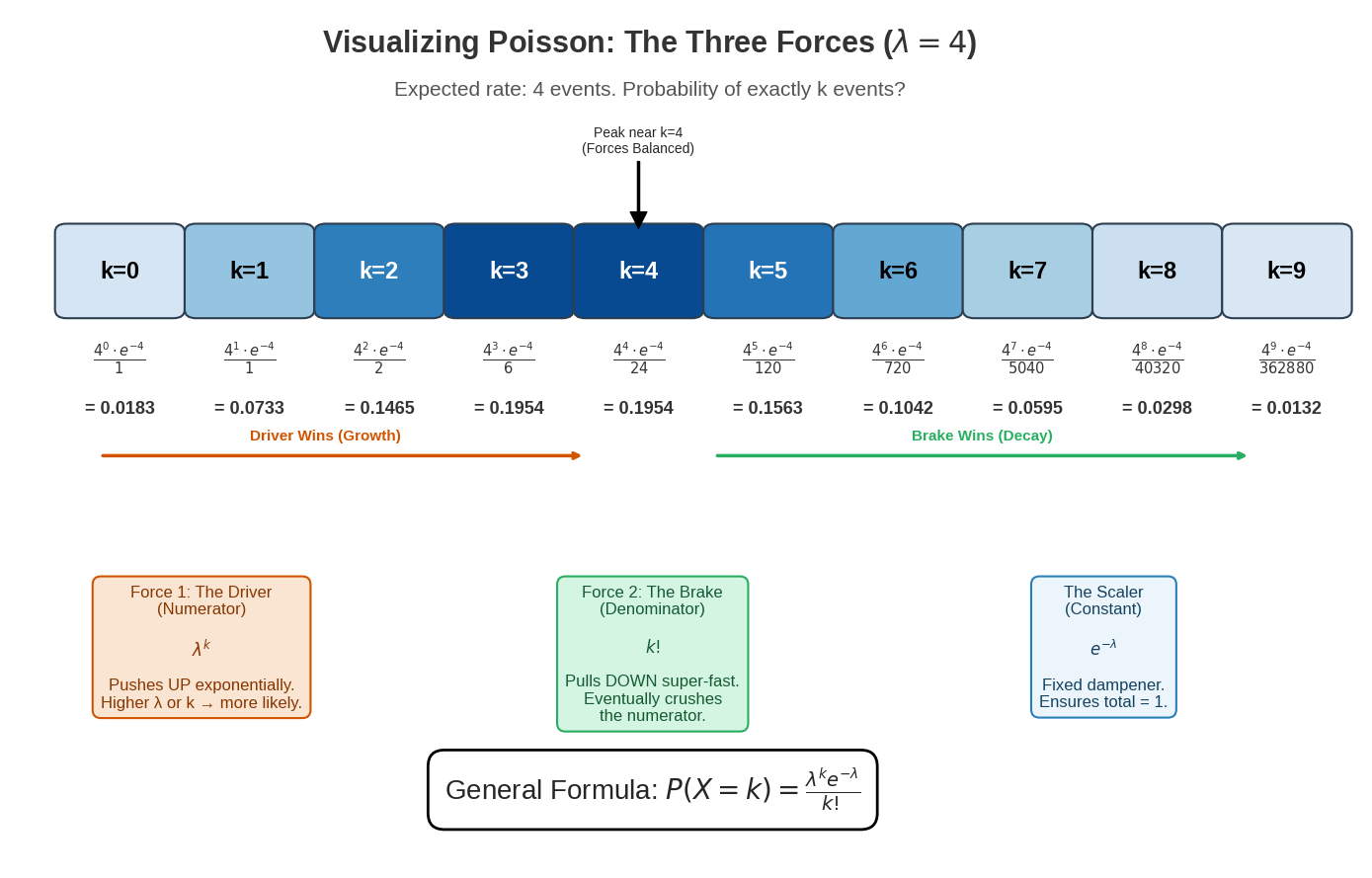

Algorithm visualization: The following diagram visualizes the Poisson formula as competing forces, building intuition for why each component exists:

The diagram above visualizes the Poisson distribution (λ = 4) using a three forces metaphor that explains how each component of the formula shapes the probability distribution:

The Three Forces:

The Driver (Numerator: ) — Shown in the orange box, this force pushes probabilities UP exponentially. As k increases, the numerator grows rapidly when λ is large. This represents the “raw likelihood” of k events based on the rate λ.

The Brake (Denominator: ) — Shown in the green box, this force pulls probabilities DOWN super-exponentially. Factorial growth eventually crushes the numerator for large k values, causing the rapid decay in the right tail of the distribution.

The Scaler (Constant: ) — Shown in the blue box, this is a fixed dampening factor that normalizes the distribution to ensure all probabilities sum to 1.

Reading the Diagram:

Color-coded boxes (k=0 through k=9): Darker blue indicates higher probability. Each box shows the formula and exact probability for that k value.

Orange arrow (“Driver Wins”): In the left portion (k < λ), the numerator grows faster than the denominator, causing probabilities to increase.

Green arrow (“Brake Wins”): In the right portion (k > λ), the factorial denominator overwhelms the numerator, causing probabilities to decay rapidly.

Peak indicator: Shows where the forces balance at k ≈ λ, marking the mode of the distribution. For λ = 4, the peak occurs at k = 4 with probability ≈ 0.195 (19.5%).

This “tug-of-war” between the driver and brake forces creates the characteristic bell-like shape of the Poisson distribution, with the peak occurring where these forces are balanced.

Key Characteristics

Scenarios: Emails per hour, customer arrivals per day, typos per page, emergency calls per shift, defects per unit area

Parameter: , average number of events in the interval ()

Random Variable:

Mean:

Variance:

Standard Deviation:

Note: Mean and variance are equal in a Poisson distribution, so the standard deviation is simply the square root of λ.

Relationship to Other Distributions: The Poisson distribution is an approximation to the Binomial distribution when is large, is small, and is moderate. Rule of thumb: use Poisson approximation when and .

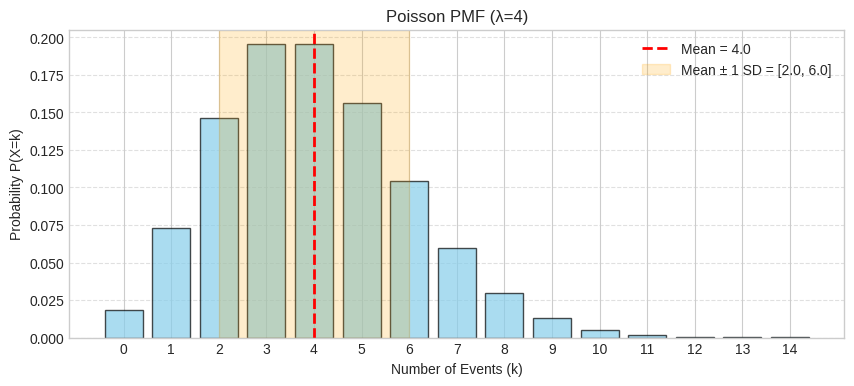

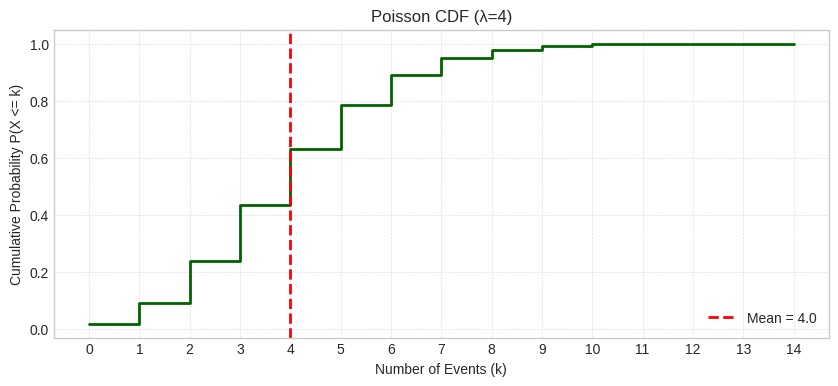

Visualizing the Distribution

Let’s visualize a Poisson distribution with (our call center example):

The PMF shows the distribution centered around λ = 4 with reasonable probability for nearby values. The shaded region shows mean ± 1 standard deviation ().

The CDF shows P(X ≤ k), useful for questions like “What’s the probability of 6 or fewer calls?” The red dashed line marks the mean.

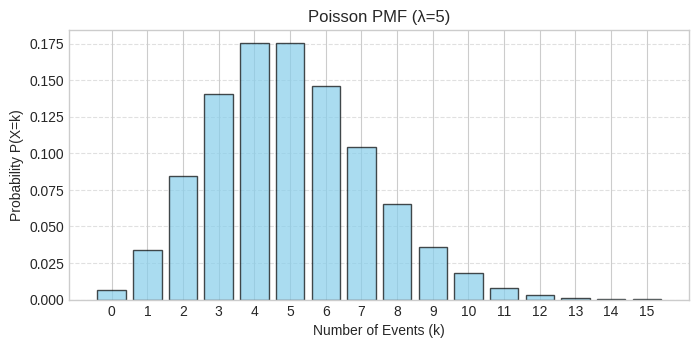

Modeling the number of emails received per hour with an average rate of λ = 5 emails/hour.

Let’s use scipy.stats.poisson to calculate the probability of observing different numbers of events and verify that the mean equals the variance.

Setting up the distribution:

We create a Poisson distribution with rate parameter λ = 5 (average 5 emails per hour):

import numpy as np

from scipy import stats

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Using scipy.stats.poisson

lambda_rate = 5

poisson_rv = stats.poisson(mu=lambda_rate)Calculating specific probabilities using the PMF:

What’s the probability of receiving exactly 3 emails in a given hour?

# PMF: Probability of exactly k events

k_events = 3

print(f"P(X={k_events} emails in an hour | lambda={lambda_rate}): {poisson_rv.pmf(k_events):.4f}")P(X=3 emails in an hour | lambda=5): 0.1404

There’s a 14.04% chance of receiving exactly 3 emails. This is below the mean of 5, so it’s less likely than values closer to 5.

Calculating cumulative probabilities using the CDF:

What’s the probability of receiving 6 or fewer emails in an hour?

# CDF: Probability of k or fewer events

k_or_fewer_events = 6

print(f"P(X <= {k_or_fewer_events} emails in an hour): {poisson_rv.cdf(k_or_fewer_events):.4f}")

print(f"P(X > {k_or_fewer_events} emails in an hour): {1 - poisson_rv.cdf(k_or_fewer_events):.4f}")

print(f"P(X > {k_or_fewer_events} emails in an hour) (using sf): {poisson_rv.sf(k_or_fewer_events):.4f}")P(X <= 6 emails in an hour): 0.7622

P(X > 6 emails in an hour): 0.2378

P(X > 6 emails in an hour) (using sf): 0.2378

There’s a 76.22% chance of receiving 6 or fewer emails, which means a 23.78% chance of receiving more than 6 emails in an hour.

Verifying the key Poisson property: mean equals variance:

A unique property of the Poisson distribution is that E[X] = Var(X) = λ:

# Mean and Variance

print(f"Mean (Expected number of emails): {poisson_rv.mean():.2f}")

print(f"Variance: {poisson_rv.var():.2f}")Mean (Expected number of emails): 5.00

Variance: 5.00

As expected, both the mean and variance equal 5.00, confirming the theoretical property of the Poisson distribution.

Generating random samples:

We can simulate many one-hour periods to see the variation in email arrivals:

# Generate random samples

n_simulations = 1000

samples = poisson_rv.rvs(size=n_simulations)

# print(f"\nSimulated number of emails per hour ({n_simulations} simulations): {samples[:20]}...")These 1000 samples represent different hours, each showing how many emails arrived during that hour.

Visualizing the PMF:

Let’s see the full probability distribution for different email counts:

# Plotting the PMF

k_values = np.arange(0, 16) # Plot for k=0 to 15

pmf_values = poisson_rv.pmf(k_values)

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 3.5))

plt.bar(k_values, pmf_values, color='skyblue', edgecolor='black', alpha=0.7)

plt.title(f"Poisson PMF (λ={lambda_rate})")

plt.xlabel("Number of Events (k)")

plt.ylabel("Probability P(X=k)")

plt.xticks(k_values)

plt.grid(axis='y', linestyle='--', alpha=0.6)

plt.show()

The PMF shows the distribution centered around λ = 5 emails, with highest probabilities at k = 4 and k = 5. The distribution is roughly symmetric for this value of λ. Values far from 5 (like 0-1 or 11+) have very low probabilities. Notice how the probability at k = 3 (which we calculated as 0.1404) appears as a moderate-height bar.

Visualizing the CDF:

The cumulative distribution helps answer questions about ranges of email counts:

# Plotting the CDF

cdf_values = poisson_rv.cdf(k_values)

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 3.5))

plt.step(k_values, cdf_values, where='post', color='darkgreen', linewidth=2)

plt.title(f"Poisson CDF (λ={lambda_rate})")

plt.xlabel("Number of Events (k)")

plt.ylabel("Cumulative Probability P(X <= k)")

plt.xticks(k_values)

plt.grid(True, which='both', linestyle='--', linewidth=0.5, alpha=0.6)

plt.show()

The CDF shows P(X ≤ k), the cumulative probability. We can see that by k = 6, the CDF reaches about 0.76 (matching our earlier calculation of 76.22%), and by k = 10, it’s close to 1.0, meaning it’s very unlikely to receive more than 10 emails in an hour.

Quick Check Questions

A call center receives an average of 12 calls per hour. What distribution models the number of calls in one hour and what is the parameter?

Answer

Poisson distribution with λ = 12 - Events occurring at a constant average rate in a fixed interval.

For a Poisson distribution with λ = 7, what are the mean and variance?

Answer

Mean = 7, Variance = 7 - For Poisson, both equal λ. This is a unique property of the Poisson distribution.

You count the number of typos on a random page of a book. The average is 2 typos per page. Which distribution?

Answer

Poisson with λ = 2 - Counting discrete events (typos) occurring in a fixed space (one page) at a constant average rate.

This fits Poisson’s requirements:

Events happen independently

Constant average rate

Counting occurrences in fixed interval/space

True or False: In a Poisson distribution, the mean can be different from the variance.

Answer

False - A key property of Poisson is that mean = variance = λ.

This property can help you identify when Poisson might not be the best fit. If your data has variance much larger or smaller than the mean, consider other distributions (e.g., Negative Binomial for overdispersion).

When can Poisson approximate Binomial?

Answer

When n is large, p is small, and np is moderate - Specifically:

n ≥ 20 and p ≤ 0.05, or

n ≥ 100 and np ≤ 10

Then Binomial(n, p) ≈ Poisson(λ = np)

Example: Binomial(n=1000, p=0.003) ≈ Poisson(λ=3)

This works because rare events in many trials behave like events occurring at a constant rate.

6. Hypergeometric Distribution¶

The Hypergeometric distribution models the number of successes in a sample drawn without replacement from a finite population. This is different from Binomial, which assumes sampling with replacement (or infinite population).

Concrete Example

You draw 5 cards from a standard deck of 52 cards. How many Aces will you get?

We model this with a random variable :

= the number of Aces in the 5-card hand

Population: N = 52 cards total

Successes in population: K = 4 Aces

Sample size: n = 5 cards drawn

can take values 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 (can’t get more than 4 Aces!)

The Hypergeometric PMF

For sampling without replacement:

This is: (ways to choose k successes from K) × (ways to choose n-k failures from N-K) / (total ways to choose n items from N).

The Hypergeometric formula uses counting principles:

(denominator): Total ways to choose items from - this is all possible samples

(numerator): Ways to choose successes from the successes available

(numerator): Ways to choose failures from the failures available

Example: Drawing 5 cards hoping for 2 Aces (N=52, K=4, n=5, k=2):

Ways to choose 2 Aces from 4:

Ways to choose 3 non-Aces from 48:

Ways to choose any 5 cards:

Probability:

The formula is essentially: (favorable outcomes) / (total possible outcomes) from basic probability, using combinations to count!

Key Characteristics

Scenarios: Cards from a deck, defective items in small batch, tagged fish in sample, jury selection from finite pool

Parameters:

: total population size

: total number of successes in population

: sample size ()

Random Variable: , bounded by

Mean:

Variance:

Standard Deviation:

The term is the finite population correction factor. As , this approaches 1, and Hypergeometric → Binomial with .

Visualizing the Distribution

Let’s visualize a Hypergeometric distribution with N=52, K=4, n=5 (our card example):

The PMF shows most likely to get 0 Aces (about 0.66 probability), less likely to get 1 or 2. The red dashed line marks the mean, and the orange shaded region shows mean ± 1 standard deviation.

The CDF shows P(X ≤ k), useful for questions like “What’s the probability of getting at most 1 Ace?” The red dashed line marks the mean.

Modeling the number of winning lottery tickets in a sample of 10 drawn from a box of 100 tickets where 20 are winners.

We’ll use scipy.stats.hypergeom to calculate probabilities for sampling without replacement and see how the mean relates to the population proportion.

Setting up the distribution:

We create a hypergeometric distribution for drawing without replacement:

import numpy as np

from scipy import stats

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Using scipy.stats.hypergeom

N_population = 100

K_successes_pop = 20

n_sample = 10

hypergeom_rv = stats.hypergeom(M=N_population, n=K_successes_pop, N=n_sample)Calculating specific probabilities using the PMF:

What’s the probability of getting exactly 3 winning tickets when we draw 10?

# PMF: Probability of exactly k successes in the sample

k_successes_sample = 3

print(f"P(X={k_successes_sample} winning tickets in sample of {n_sample}): {hypergeom_rv.pmf(k_successes_sample):.4f}")P(X=3 winning tickets in sample of 10): 0.2092

There’s a 20.13% chance of getting exactly 3 winners. This is higher than the probability of getting 2 winners because 3 is closer to the expected value (see below).

Calculating cumulative probabilities using the CDF:

What’s the probability of getting 2 or fewer winning tickets?

# CDF: Probability of k or fewer successes in the sample

k_or_fewer_sample = 2

print(f"P(X <= {k_or_fewer_sample} winning tickets in sample): {hypergeom_rv.cdf(k_or_fewer_sample):.4f}")

print(f"P(X > {k_or_fewer_sample} winning tickets in sample): {1 - hypergeom_rv.cdf(k_or_fewer_sample):.4f}")

print(f"P(X > {k_or_fewer_sample} winning tickets in sample) (using sf): {hypergeom_rv.sf(k_or_fewer_sample):.4f}")P(X <= 2 winning tickets in sample): 0.6812

P(X > 2 winning tickets in sample): 0.3188

P(X > 2 winning tickets in sample) (using sf): 0.3188

There’s a 67.67% chance of getting 2 or fewer winners, which means a 32.33% chance of getting more than 2.

Computing mean and variance:

Let’s verify the mean matches the expected proportion from the population:

# Mean and Variance

print(f"Mean (Expected number of winning tickets in sample): {hypergeom_rv.mean():.2f}")

print(f"Variance: {hypergeom_rv.var():.2f}")

print(f"Standard Deviation: {hypergeom_rv.std():.2f}")

# Theoretical mean: E[X] = n * (K/N) = 10 * (20/100) = 2.0Mean (Expected number of winning tickets in sample): 2.00

Variance: 1.45

Standard Deviation: 1.21

As expected, the mean is 2.0 winners, which is exactly n × (K/N) = 10 × (20/100) = 10 × 0.2. Since 20% of the population are winners, we expect 20% of our sample to be winners. The finite population correction makes the variance (1.44) smaller than it would be for binomial sampling with replacement.

Generating random samples:

We can simulate many draws of 10 tickets:

# Generate random samples

n_simulations = 1000

samples = hypergeom_rv.rvs(size=n_simulations)

# print(f"\nSimulated number of winning tickets ({n_simulations} simulations): {samples[:20]}...")These 1000 samples represent different sets of 10 tickets drawn from the box, showing natural variation in outcomes.

Visualizing the PMF:

Let’s see the distribution of possible outcomes when drawing 10 tickets:

The PMF is centered around 2 winners (the expected value), with highest probabilities at 1, 2, and 3 winners. Getting 0 winners or 5+ winners is much less likely. The distribution looks roughly bell-shaped, which is typical for hypergeometric distributions when the sample size is small relative to the population. Notice that k = 3 (which we calculated as 20.13%) appears as one of the tallest bars.

Visualizing the CDF:

The cumulative distribution shows the total probability of getting up to k winners:

The CDF shows the cumulative probability. We can see that P(X ≤ 2) ≈ 0.68 (matching our earlier calculation of 67.67%), and by k = 5, nearly all probability has accumulated (close to 1.0).

Quick Check Questions

You draw 7 cards from a deck of 52. You want to know how many hearts you get. What distribution models this and what are the parameters?

Answer

Hypergeometric with N=52, K=13, n=7 - Sampling without replacement from a finite population (13 hearts in 52 cards).

For a Hypergeometric distribution with N=50, K=10, n=5, what is the expected value (mean)?

Answer

E[X] = n(K/N) = 5 × (10/50) = 1 - Expected number of successes in the sample.

A quality inspector randomly selects 10 products from a batch of 100 (where 15 are defective) without replacement. Which distribution?

Answer

Hypergeometric with N=100, K=15, n=10 - Sampling without replacement from a finite population.

This is NOT Binomial because:

We’re sampling without replacement

The sample size (10) is significant relative to population (100)

Each draw changes the probability for subsequent draws

What’s the key difference between Binomial and Hypergeometric distributions?

Answer

Hypergeometric samples WITHOUT replacement (finite population), while Binomial samples WITH replacement (or assumes infinite population).

Key implications:

Hypergeometric: Trials are NOT independent (each draw affects the next)

Binomial: Trials ARE independent (constant probability p)

Rule of thumb: If N > 20n, Hypergeometric ≈ Binomial because the sample is small relative to the population.

When can Hypergeometric be approximated by Binomial?

Answer

When the population is much larger than the sample - Specifically, when N > 20n.

In this case, Hypergeometric(N, K, n) ≈ Binomial(n, p=K/N)

Example: Drawing 10 cards from a population of 1000 cards. The small sample barely affects the population proportions, so with/without replacement gives nearly identical results.

7. Discrete Uniform Distribution¶

The Discrete Uniform distribution models selecting one outcome from a finite set where all outcomes are equally likely.

Concrete Example

Suppose you roll a fair six-sided die. Each face (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6) has an equal probability of appearing.

We model this with a random variable :

= the number showing on the die

can take values 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

The probabilities are:

The Discrete Uniform PMF

For a Discrete Uniform distribution on the integers from to (inclusive):

For our die example with and :

for

The Discrete Uniform distribution is the simplest probability distribution:

Total outcomes: (the “+1” counts both endpoints)

Each outcome equally likely: Probability =

Example: For values 5 through 15:

Total values: values

Each has probability:

This directly implements the classical definition of probability: (favorable outcomes) / (total equally likely outcomes).

Key Characteristics

Scenarios: Fair die roll, random selection from a list, lottery number selection, random password digit

Parameters:

: minimum value (integer)

: maximum value (integer, )

Random Variable:

Mean:

Variance:

Standard Deviation:

Relationship to Other Distributions: The Discrete Uniform distribution is a special case of the Categorical distribution where all categories have equal probability . If outcomes aren’t equally likely, use Categorical instead.

Visualizing the Distribution

Let’s visualize a Discrete Uniform distribution for a fair die (, ):

The PMF shows six equal bars, each with probability 1/6, representing the fair die. The shaded region shows mean ± 1 standard deviation.

The CDF increases in equal steps of 1/6 at each value, reaching 1.0 at the maximum value. The red dashed line marks the mean.

Modeling a random integer selection from 1 to 20, where each number is equally likely to be chosen.

Let’s use scipy.stats.randint to calculate probabilities and generate samples.

Setting up the distribution:

We create a discrete uniform distribution over integers from 1 to 20 (note: scipy.stats.randint uses half-open intervals [low, high)):

import numpy as np

from scipy import stats

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Using scipy.stats.randint (note: uses [low, high) interval)

a_sel = 1

b_sel = 20

uniform_rv = stats.randint(low=a_sel, high=b_sel+1)Calculating probabilities using the PMF:

Since all values are equally likely, each value has the same probability:

# PMF: Probability of any specific value

k_val = 7

print(f"P(X={k_val}): {uniform_rv.pmf(k_val):.4f}")

print(f"This equals 1/{b_sel-a_sel+1} = {1/(b_sel-a_sel+1):.4f}")P(X=7): 0.0500

This equals 1/20 = 0.0500

Each of the 20 values has probability 1/20 = 0.05. The value 7 has the same probability as any other value.

Calculating cumulative probabilities using the CDF:

What’s the probability of selecting a number ≤ 10?

# CDF: Probability of k or fewer

k_threshold = 10

print(f"P(X <= {k_threshold}): {uniform_rv.cdf(k_threshold):.4f}")

print(f"P(X > {k_threshold}): {uniform_rv.sf(k_threshold):.4f}")P(X <= 10): 0.5000

P(X > 10): 0.5000

There’s a 50% chance of selecting 10 or less (values 1-10), and a 50% chance of selecting more than 10 (values 11-20). This makes sense since 10 is the midpoint.

Computing mean and variance:

Let’s verify the mean is at the center of the range:

# Mean and Variance

print(f"Mean (Expected value): {uniform_rv.mean():.2f}")

print(f"Theoretical mean (a+b)/2: {(a_sel+b_sel)/2:.2f}")

print(f"Variance: {uniform_rv.var():.2f}")Mean (Expected value): 10.50

Theoretical mean (a+b)/2: 10.50

Variance: 33.25

The mean is 10.50, exactly halfway between 1 and 20, as expected from the formula (a+b)/2 = (1+20)/2 = 10.5.

Generating random samples:

Let’s generate 10 random selections:

# Generate random samples

n_samples = 10

samples = uniform_rv.rvs(size=n_samples)

print(f"{n_samples} random selections from 1 to {b_sel}:")

print(samples)10 random selections from 1 to 20:

[17 13 12 18 1 11 10 10 14 20]

Each sample is an independent random selection, all values equally likely.

Visualizing the PMF:

The PMF visualization shows the defining characteristic of the uniform distribution—perfect equality:

All 20 values have equal probability of 0.05 (1/20). This flat distribution is the signature of the discrete uniform—no value is more likely than any other.

Visualizing the CDF:

The CDF shows a perfect linear staircase:

The CDF increases in equal steps of 1/20 = 0.05, perfectly linear. At k=10, the CDF is exactly 0.5 (the median), confirming our earlier calculation.

Quick Check Questions

You randomly select a card from a standard deck (52 cards). If X represents the card number (1-13, where 1=Ace, 11=Jack, 12=Queen, 13=King), what distribution models this and what are the parameters?

Answer

Discrete Uniform distribution with a = 1, b = 13 - Each card number is equally likely (4 of each in the deck).

For a Discrete Uniform distribution with a = 5 and b = 15, what is the probability of getting exactly 10?

Answer

P(X = 10) = 1/(15-5+1) = 1/11 ≈ 0.091 - All values in the range are equally likely.

What is the mean of a Discrete Uniform distribution on the integers from 1 to 100?

Answer

Mean = (1+100)/2 = 50.5 - The mean is the midpoint of the range.

You’re modeling the outcome of rolling a fair six-sided die. Should you use Discrete Uniform or Categorical distribution?

Answer

Discrete Uniform distribution - Since it’s a fair die, all outcomes (1-6) are equally likely with probability 1/6 each.

Use Discrete Uniform(a=1, b=6).

Note: If the die were loaded (unequal probabilities), you’d use the Categorical distribution instead.

For a Discrete Uniform distribution on integers from a to b, why is the variance equal to ?

Answer

The variance formula reflects how spread out the values are:

Larger range (b-a): Higher variance - values are more spread out

Formula intuition: The variance grows with the square of the range, similar to continuous uniform distributions

Example:

Discrete Uniform(1, 6): Variance = (6-1)(6-1+2)/12 = 5×7/12 ≈ 2.92

Discrete Uniform(1, 100): Variance = 99×101/12 ≈ 833.25

Much larger range → much larger variance.

8. Categorical Distribution¶

The Categorical distribution models a single trial with multiple possible outcomes (more than 2), where each outcome has its own probability. It’s the generalization of the Bernoulli distribution to more than two categories.

Concrete Example

Suppose you’re rolling a loaded six-sided die where the faces have different probabilities:

Face 1: probability 0.1

Face 2: probability 0.15

Face 3: probability 0.20

Face 4: probability 0.25

Face 5: probability 0.20

Face 6: probability 0.10

We model this with a random variable :

= the face that appears

can take values in

Each value has its own probability: etc.

The Categorical PMF

For a Categorical distribution with possible outcomes and probabilities where :

For our loaded die example:

Sum: ✓

The Categorical PMF is straightforward - each outcome has its own assigned probability:

Single trial: Only one outcome occurs

Each outcome has probability : Directly specified

Constraint: All probabilities must sum to 1 (ensuring exactly one outcome occurs)

This is the most general discrete distribution for a single trial - every outcome can have a different probability. It generalizes simpler distributions:

If : Reduces to Bernoulli

If all : Reduces to Discrete Uniform

Key Characteristics

Scenarios: Loaded die, customer choosing from menu categories, survey response (multiple choice), weather outcome (sunny/cloudy/rainy/snowy)

Parameters:

: number of categories

: probabilities for each category (must sum to 1)

Random Variable:

Mean: (weighted average of outcomes)

Variance:

Relationship to Other Distributions: Categorical generalizes Bernoulli (when ) and is a special case of Discrete Uniform (when all are equal). For multiple trials, use the Multinomial distribution instead.

Visualizing the Distribution

Let’s visualize our loaded die Categorical distribution:

The PMF shows the different probabilities for each face of the loaded die.

The CDF increases by different amounts at each value, reflecting the varying probabilities.

A coffee shop tracks customer drink preferences: 40% choose coffee, 30% choose tea, 20% choose juice, and 10% choose water.

Let’s model this using a Categorical distribution with scipy.stats.rv_discrete.

Setting up the distribution:

We create a categorical distribution with custom probabilities for each category:

import numpy as np

from scipy import stats

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Define the categorical distribution

choices = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4]) # 1=Coffee, 2=Tea, 3=Juice, 4=Water

probs = np.array([0.40, 0.30, 0.20, 0.10])

categorical_rv = stats.rv_discrete(values=(choices, probs))Displaying probabilities:

Let’s see the probability of each drink choice:

# PMF: Probability of each choice

labels = ['Coffee', 'Tea', 'Juice', 'Water']

for i, (choice, label) in enumerate(zip(choices, labels)):

print(f"P(X={choice}) [{label}]: {probs[i]:.2f}")P(X=1) [Coffee]: 0.40

P(X=2) [Tea]: 0.30

P(X=3) [Juice]: 0.20

P(X=4) [Water]: 0.10

Coffee is the most likely choice (40%), followed by tea (30%), juice (20%), and water (10%). Unlike the uniform distribution, these probabilities differ.

Calculating cumulative probabilities:

What’s the probability a customer chooses coffee or tea (categories 1 or 2)?

# CDF: Probability of choice i or lower

print(f"P(X <= 2) [Coffee or Tea]: {categorical_rv.cdf(2):.2f}")

print(f"P(X > 2) [Juice or Water]: {1 - categorical_rv.cdf(2):.2f}")P(X <= 2) [Coffee or Tea]: 0.70

P(X > 2) [Juice or Water]: 0.30

There’s a 70% chance the customer chooses coffee or tea, and a 30% chance they choose juice or water.

Computing mean and variance:

While mean and variance are less interpretable for categorical data with arbitrary numbering, scipy can compute them:

# Mean and Variance

print(f"Mean (Expected value): {categorical_rv.mean():.2f}")

print(f"Variance: {categorical_rv.var():.2f}")Mean (Expected value): 2.00

Variance: 1.00

The mean of 2.00 indicates choices are weighted toward lower category numbers (coffee and tea).

Generating random samples:

Let’s simulate 100 customers and see how many choose each drink:

# Generate random samples

n_customers = 100

samples = categorical_rv.rvs(size=n_customers)

print(f"\nSimulated choices for {n_customers} customers:")

for i, label in enumerate(labels, 1):

count = np.sum(samples == i)

print(f"{label}: {count} ({count/n_customers:.1%})")

Simulated choices for 100 customers:

Coffee: 38 (38.0%)

Tea: 35 (35.0%)

Juice: 20 (20.0%)

Water: 7 (7.0%)

The simulated counts should approximate the theoretical probabilities (40%, 30%, 20%, 10%), with some random variation.

Visualizing the PMF:

The bar chart clearly shows the different probabilities for each category:

The PMF shows unequal bar heights, distinguishing this from a discrete uniform distribution. Coffee (40%) has the tallest bar, while water (10%) has the shortest, clearly visualizing customer preferences.

The CDF shows cumulative probabilities across the ordered choices.

Quick Check Questions

A traffic light can be red (50%), yellow (10%), or green (40%). What distribution models the color when you arrive at an intersection?

Answer

Categorical distribution with k=3 categories and probabilities p₁=0.5, p₂=0.1, p₃=0.4 - Single trial with three possible outcomes.

For a Categorical distribution with 4 equally likely outcomes, what is P(X = 2)?

Answer

P(X = 2) = 0.25 - For equally likely outcomes, each has probability 1/4.

How is the Categorical distribution related to the Bernoulli distribution?

Answer

Bernoulli is a special case of Categorical with k=2 - When there are only two categories, Categorical reduces to Bernoulli.

Categorical generalizes Bernoulli from 2 outcomes to k outcomes.

You’re observing a single customer’s choice from a menu with 5 items having probabilities [0.3, 0.25, 0.2, 0.15, 0.1]. Should you use Categorical or Multinomial distribution?

Answer

Categorical distribution - You’re observing a single trial (one customer making one choice).

Key distinction:

Categorical: Single trial, multiple outcomes (this scenario)

Multinomial: Multiple trials, counting how many times each outcome occurs

If you observed 100 customers and counted how many chose each item, that would be Multinomial.

When can you model a Categorical distribution as a Discrete Uniform distribution?

Answer

When all k categories have equal probability - If p₁ = p₂ = ... = pₖ = 1/k.

Example:

Rolling a fair die (6 equally likely outcomes): Can use either Categorical(p=[1/6, 1/6, 1/6, 1/6, 1/6, 1/6]) or Discrete Uniform(a=1, b=6)

Rolling a loaded die (unequal probabilities): Must use Categorical

Discrete Uniform is just a special case of Categorical where all probabilities are equal.

9. Multinomial Distribution¶

The Multinomial distribution models performing a fixed number of independent trials where each trial has multiple possible outcomes (more than 2), and we count how many times each outcome occurs. It’s the generalization of the Binomial distribution to more than two categories.

Concrete Example

Suppose you roll a fair six-sided die 20 times. We want to know how many times each face (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6) appears.

We model this with a random vector where:

= number of times face 1 appears

= number of times face 2 appears

... and so on

Constraint:

The probabilities for a fair die are:

The Multinomial PMF

For independent trials with possible outcomes and probabilities where :

where .

The term is the multinomial coefficient (see Chapter 3: Permutations of Identical Objects).

For our die example, the probability of getting exactly (3, 4, 2, 5, 4, 2) of each face:

The Multinomial formula extends the Binomial idea to multiple categories:

: The multinomial coefficient counts how many different sequences of trials produce exactly occurrences of category 1, of category 2, etc.

: Probability of any specific sequence with those counts

Example: With 3 trials and outcomes (A, A, B):

There are arrangements: AAB, ABA, BAA

Each has probability

Combined:

The multinomial coefficient is like the binomial coefficient, but for distributing items among categories instead of just 2.

Key Characteristics

Scenarios: Rolling a die n times (counting each face), survey with multiple choice options, customer purchases across product categories, DNA base frequencies in a sequence

Parameters:

: number of trials

: number of categories

: probabilities for each category (must sum to 1)

Random Variables: where = count for category , and

Mean for each category:

Variance for each category:

Relationship to Other Distributions: Multinomial generalizes Binomial (when ) and Categorical (single trial becomes multiple trials). Each individual category count follows a Binomial distribution with parameters .

Visualizing the Distribution

Multinomial distributions are challenging to visualize since they involve multiple variables. Let’s look at a simple case with categories:

The marginal distribution of any single category in a Multinomial distribution is actually a Binomial distribution! Here, Category 1 follows Binomial(n=15, p=1/3).

Connecting to our die example: We simplified to 3 categories for easier visualization, but the same principle applies to our 6-sided die example (n=20 rolls). Each face count would follow Binomial(n=20, p=1/6). The histogram would be similar but centered around 20/6 ≈ 3.33 instead of 15/3 = 5.

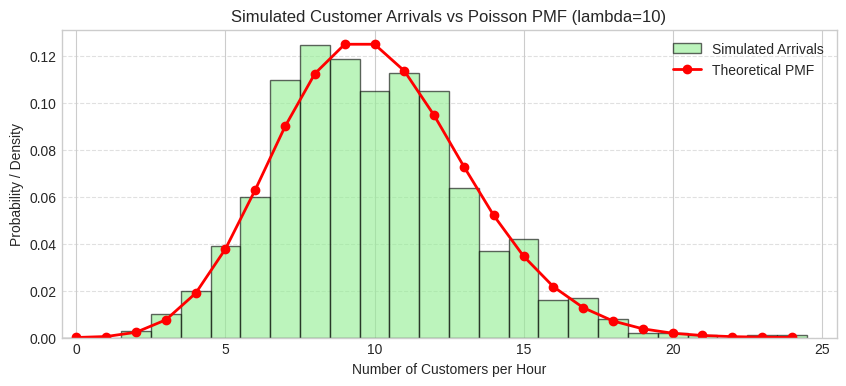

A store tracks purchases across 4 product categories: Electronics (30%), Clothing (25%), Home Goods (25%), Food (20%). We observe 50 customers and count how many purchase from each category.

Let’s use numpy.random.multinomial to work with this distribution.

Setting up parameters and computing expected values:

First, let’s define our multinomial parameters and see what counts we expect:

import numpy as np

from scipy import stats

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Define parameters

n_customers = 50

categories = ['Electronics', 'Clothing', 'Home Goods', 'Food']

probs = np.array([0.30, 0.25, 0.25, 0.20])

# Expected counts

expected_counts = n_customers * probs

print("Expected purchases per category:")

for cat, exp in zip(categories, expected_counts):

print(f" {cat}: {exp:.1f}")Expected purchases per category:

Electronics: 15.0

Clothing: 12.5

Home Goods: 12.5

Food: 10.0

With 50 customers, we expect 15 to buy Electronics (30%), 12.5 each for Clothing and Home Goods (25%), and 10 for Food (20%).

Generating a single sample:

Let’s simulate one day of 50 customers and see how many purchase from each category:

# Generate one sample (one set of 50 customers)

one_sample = np.random.multinomial(n_customers, probs)

print(f"\nOne simulation of {n_customers} customers:")

for cat, count in zip(categories, one_sample):

print(f" {cat}: {count}")

print(f"Total: {np.sum(one_sample)}")

One simulation of 50 customers:

Electronics: 17

Clothing: 14

Home Goods: 10

Food: 9

Total: 50

Notice that the total is always exactly 50—every customer chooses exactly one category. The individual counts will vary around the expected values due to randomness.

Analyzing the distribution through many simulations:

Let’s simulate many days to understand the variability in each category’s count:

# Generate many samples to see the distribution

n_sims = 10000

samples = np.random.multinomial(n_customers, probs, size=n_sims)

# Compute mean and std for each category

for i, cat in enumerate(categories):

counts = samples[:, i]

print(f"{cat}:")

print(f" Mean: {np.mean(counts):.2f} (theoretical: {n_customers * probs[i]:.2f})")

print(f" Std: {np.std(counts):.2f} (theoretical: {np.sqrt(n_customers * probs[i] * (1-probs[i])):.2f})")Electronics:

Mean: 14.94 (theoretical: 15.00)

Std: 3.23 (theoretical: 3.24)

Clothing:

Mean: 12.53 (theoretical: 12.50)

Std: 3.08 (theoretical: 3.06)

Home Goods:

Mean: 12.51 (theoretical: 12.50)

Std: 3.11 (theoretical: 3.06)

Food:

Mean: 10.02 (theoretical: 10.00)

Std: 2.83 (theoretical: 2.83)

The simulated means should closely match the theoretical values (n × p_i), and the standard deviations follow the binomial formula √(n × p_i × (1-p_i)) since each category’s marginal distribution is binomial.

Visualizing the marginal distributions:

Let’s plot the distribution of counts for each category separately:

Each subplot shows one category’s distribution across 10,000 simulations. The histograms are bell-shaped and centered on the expected values (red dashed lines). Electronics (p=0.30) has the highest expected count (15), while Food (p=0.20) has the lowest (10). Each category’s marginal distribution is binomial with parameters (n=50, p=category probability), but importantly, these counts are NOT independent—they must sum to 50.

Quick Check Questions

You flip a fair coin 30 times and count heads and tails. What distribution models the counts?

Answer

Multinomial distribution with n=30, k=2, and p₁=p₂=0.5 - Or equivalently, Binomial(n=30, p=0.5) for the number of heads, since there are only 2 categories.

When k=2, Multinomial is the same as Binomial.

For a Multinomial distribution with n=100 trials and k=4 equally likely categories, what is the expected count for any one category?

Answer

E[X_i] = n × p_i = 100 × 0.25 = 25 - Each category is expected to appear 25 times.

Since all 4 categories are equally likely, p_i = 1/4 = 0.25 for each.

How is the Multinomial distribution related to the Binomial distribution?

Answer

Binomial is a special case of Multinomial with k=2 - When there are only two categories, Multinomial reduces to Binomial.

Multinomial generalizes Binomial from 2 outcomes to k outcomes across multiple trials.