Why you only need 23 people for a 50% chance of a shared birthday

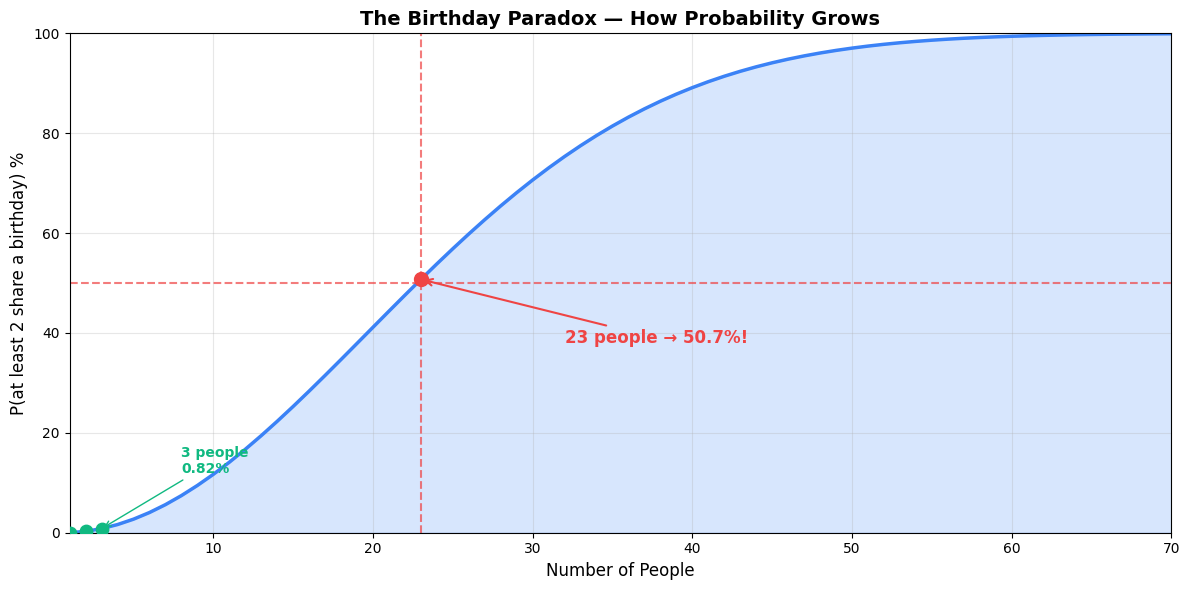

Here’s a counterintuitive fact: in a room of just 23 people, there’s a better than 50% chance that two of them share a birthday. With 70 people, it’s virtually certain (99.9%). Let’s build up to understanding why, starting from the simplest case.

The Clever Trick: Complement Counting¶

Directly counting all the ways people could share birthdays is messy — you’d have to consider pairs sharing, triplets sharing, different combinations... Instead, we flip the problem:

Calculating “no shared birthdays” is surprisingly elegant. We just need everyone to pick different days. Let’s build this up person by person.

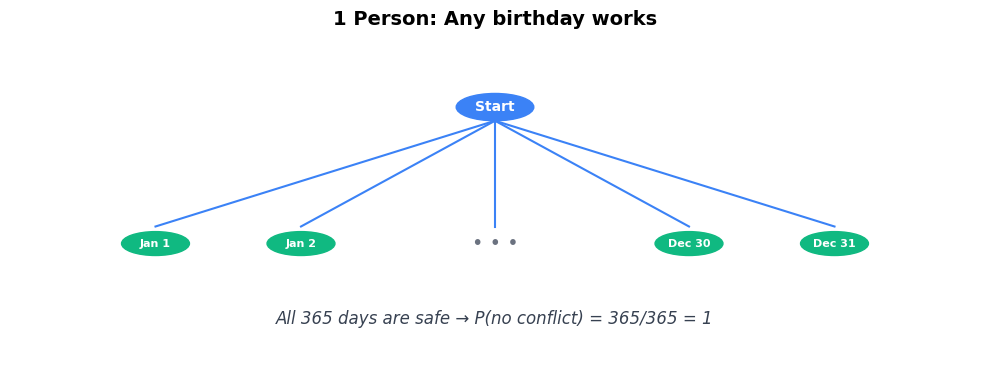

Case 1: Just One Person¶

With only one person, there’s no one to share a birthday with!

They can pick any of the 365 days — all options are “safe.”

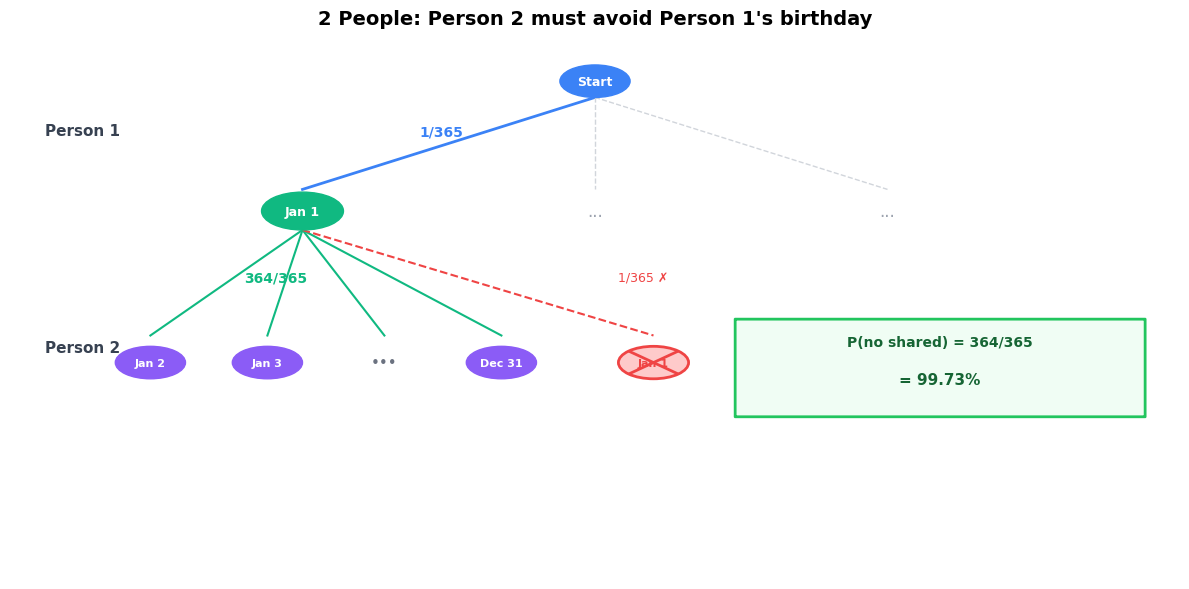

Case 2: Two People¶

Now it gets interesting. Person 1 picks any day. Person 2 must pick a different day to avoid a collision.

Person 1: 365 choices out of 365 → probability = 365/365

Person 2: 364 safe choices out of 365 → probability = 364/365

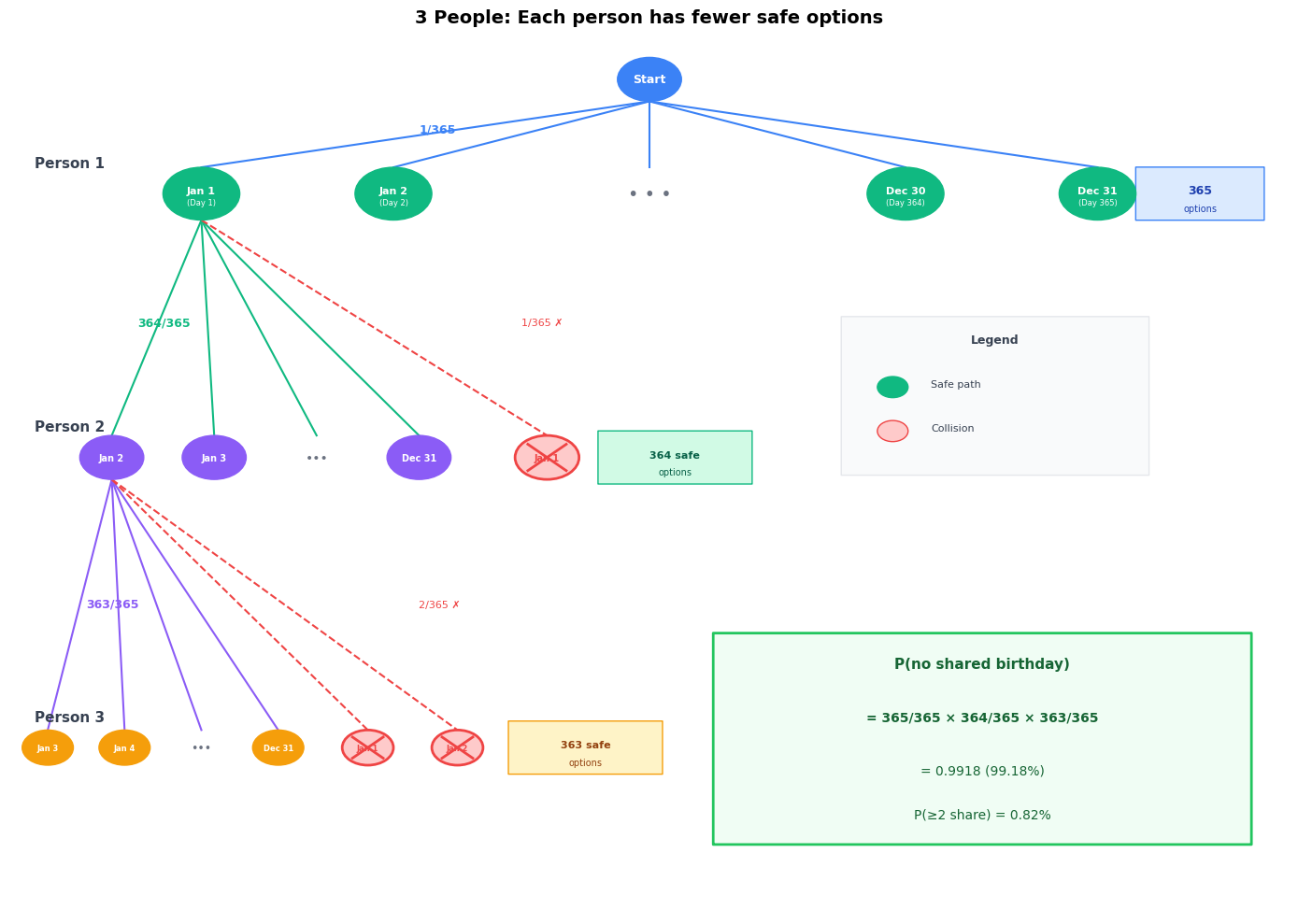

Case 3: Three People¶

Person 3 joins. Now they must avoid two birthdays.

Person 1: 365/365

Person 2: 364/365 (avoid 1 day)

Person 3: 363/365 (avoid 2 days)

The Pattern Emerges¶

Notice what’s happening:

Each new person has one fewer safe day to choose from

We multiply all the individual probabilities together

The tree has 365 × 364 × 363 valid paths out of 365³ total paths

The General Case: N People¶

For n people, the pattern continues:

Or more compactly using product notation:

What does ∏ mean? The symbol (capital Greek letter “pi”) means “product” — multiply all the terms together. It’s like (summation), but for multiplication instead of addition. Here, means “multiply the expression for each value of k from 0 to n-1.”

From Product to Factorial¶

Here’s how to get from product notation to factorial form:

Step 1: Separate the numerators and denominators (n fractions, so n terms each):

Step 2: Recognize the numerator as a “falling factorial” — it’s with the smaller terms cut off:

This works because , and dividing by cancels the tail.

Step 3: Combine:

Let’s see how this grows:

| People | P(no shared) | P(≥2 share) |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 99.73% | 0.27% |

| 3 | 99.18% | 0.82% |

| 5 | 97.29% | 2.71% |

| 10 | 88.31% | 11.69% |

| 15 | 74.71% | 25.29% |

| 20 | 58.86% | 41.14% |

| 23 | 49.27% | 50.73% ← 50%! |

| 30 | 29.37% | 70.63% |

| 40 | 10.88% | 89.12% |

| 50 | 2.96% | 97.04% |

| 70 | 0.08% | 99.92% |

The probability rises fast. Let’s visualize this:

Why Is It So Counterintuitive?¶

Our intuition fails because we think about the wrong question. We instinctively imagine:

“What’s the chance someone shares my birthday?”

That probability is low — about 6% with 23 people. Here’s why: each of the other 22 people has a 364/365 chance of not matching your birthday, so:

But the birthday paradox asks a fundamentally different question:

“What’s the chance any two people share a birthday?”

The key difference: you’re no longer special. We’re not anchoring on one person’s birthday — we’re checking every possible pair.

The Power of Pairs¶

With 23 people, there are:

Each pair is an independent opportunity for a match. Think of it like buying lottery tickets:

A single ticket (one pair) has low odds: roughly 1/365

But 253 tickets (253 pairs) give you 253 chances to win!

While the pairs aren’t truly independent (they overlap in people), the intuition holds: more pairs = more chances for a collision.

The Exponential Trap¶

Here’s another way to see it. The probability of no match drops with each person:

| People | Pairs | P(no shared) |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | 99.7% |

| 10 | 45 | 88.3% |

| 23 | 253 | 49.3% |

| 30 | 435 | 29.4% |

The pairs grow quadratically (n² growth), while our intuition thinks linearly (n growth). That’s the heart of the paradox — we underestimate how fast opportunities for coincidence multiply.

Common Mistake to Avoid¶

When computing the probability, keep the denominator as 365 throughout. A common error is writing:

But each person always chooses from 365 possible days. The shrinking numerator (365, 364, 363...) counts how many of those choices are “safe.”

Summary¶

The birthday paradox isn’t really a paradox — just a demonstration of how quickly combinatorial possibilities grow.

Key insights:

Use complement counting — Calculate P(none share) and subtract from 1

Build up person by person — Each new person narrows the safe choices by one

Multiply the probabilities — P(all different) = product of individual “safe” probabilities

Pairs grow quadratically — n people create n(n-1)/2 pairs, which is why probability rises so fast

Now you understand why, in a typical classroom of 30 students, there’s a 70% chance two people share a birthday!