Why reducing dimensions can make models more powerful

The Counterintuitive Insight¶

Here’s a puzzle: You have a massive dataset with hundreds or thousands of dimensions. Your first instinct might be to preserve all that information—surely more dimensions mean more expressive power?

But across wildly different domains of machine learning, from recommendation systems to language models, we keep seeing the same pattern: Projecting high-dimensional data into lower-dimensional spaces makes models work better.

This isn’t just about computational efficiency (though that helps). It’s about forcing models to discover the essential structure hidden in the data.

In this post, we’ll explore this principle through two seemingly unrelated examples:

Alternating Least Squares (ALS) for movie recommendations

Multi-Head Attention in transformers

By the end, you’ll understand why “less is more” when it comes to dimensions.

Part 1: The Core Principle¶

What Are Latent Factors?¶

Latent factors are hidden dimensions that capture the underlying patterns in data. They’re called “latent” (hidden) because:

They aren’t directly observed in the raw data

They’re learned automatically by algorithms

They often correspond to meaningful concepts, even though we never explicitly defined them

Think of them as the “real reasons” behind what we observe.

The Dimensionality Reduction Paradox¶

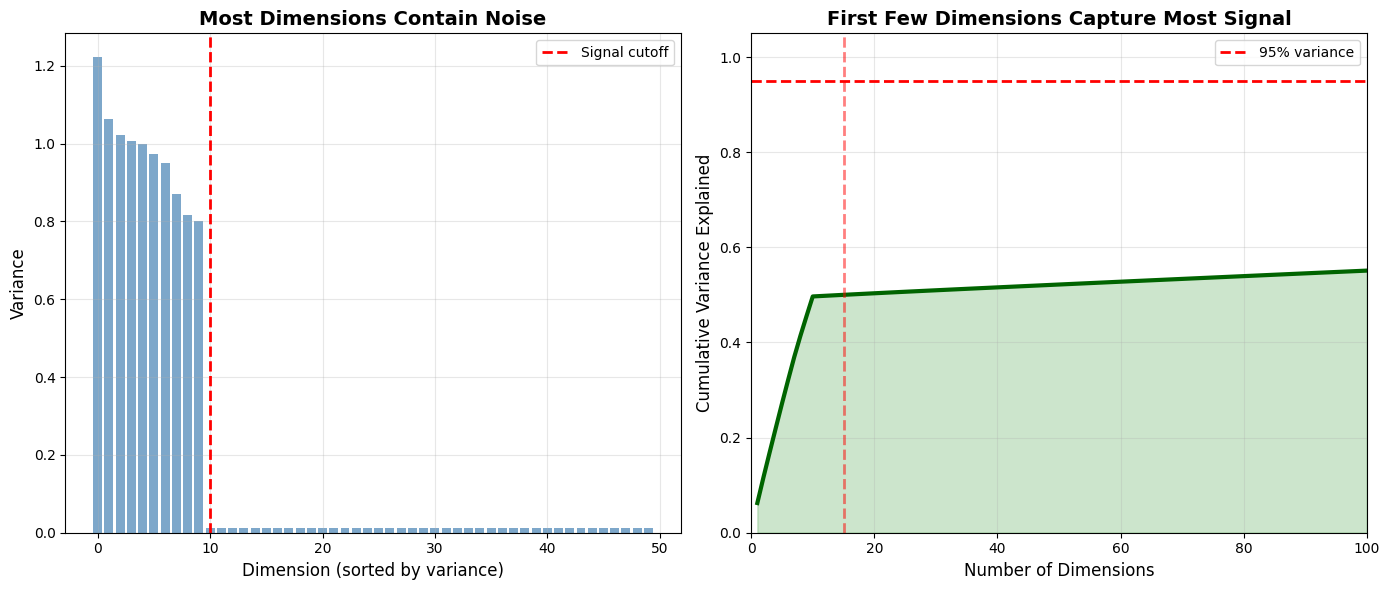

Consider a dataset with 1000 features. If we project it into just 50 dimensions, we’re throwing away 95% of the information, right?

Not quite. Here’s what actually happens:

Source

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(14, 6))

# Left: High-dimensional noise

np.random.seed(42)

n_points = 200

n_dims_high = 1000

# Generate data that mostly lies on a low-dimensional manifold + noise

true_signal = np.random.randn(n_points, 10) # 10 real dimensions

noise = np.random.randn(n_points, n_dims_high - 10) * 0.1 # 990 noise dimensions

high_dim_data = np.concatenate([true_signal, noise], axis=1)

# Calculate variance explained by each dimension

variance_explained = np.var(high_dim_data, axis=0)

sorted_variance = np.sort(variance_explained)[::-1]

cumulative_variance = np.cumsum(sorted_variance) / np.sum(sorted_variance)

ax1.bar(range(50), sorted_variance[:50], color='steelblue', alpha=0.7)

ax1.set_xlabel('Dimension (sorted by variance)', fontsize=12)

ax1.set_ylabel('Variance', fontsize=12)

ax1.set_title('Most Dimensions Contain Noise', fontsize=14, fontweight='bold')

ax1.axvline(x=10, color='red', linestyle='--', linewidth=2, label='Signal cutoff')

ax1.legend(fontsize=10)

ax1.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Right: Cumulative variance explained

ax2.plot(range(1, 101), cumulative_variance[:100], linewidth=3, color='darkgreen')

ax2.axhline(y=0.95, color='red', linestyle='--', linewidth=2, label='95% variance')

ax2.axvline(x=15, color='red', linestyle='--', linewidth=2, alpha=0.5)

ax2.fill_between(range(1, 101), 0, cumulative_variance[:100], alpha=0.2, color='green')

ax2.set_xlabel('Number of Dimensions', fontsize=12)

ax2.set_ylabel('Cumulative Variance Explained', fontsize=12)

ax2.set_title('First Few Dimensions Capture Most Signal', fontsize=14, fontweight='bold')

ax2.legend(fontsize=10)

ax2.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

ax2.set_xlim(0, 100)

ax2.set_ylim(0, 1.05)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Key Insight: Real-world data rarely uses all available dimensions meaningfully. Most “dimensions” are just noise or redundant representations of the same underlying concepts.

By projecting to lower dimensions, we’re not losing information—we’re filtering out noise and forcing the model to learn what matters.

Part 2: Example 1 - ALS for Movie Recommendations¶

The Problem: Sparse Rating Matrices¶

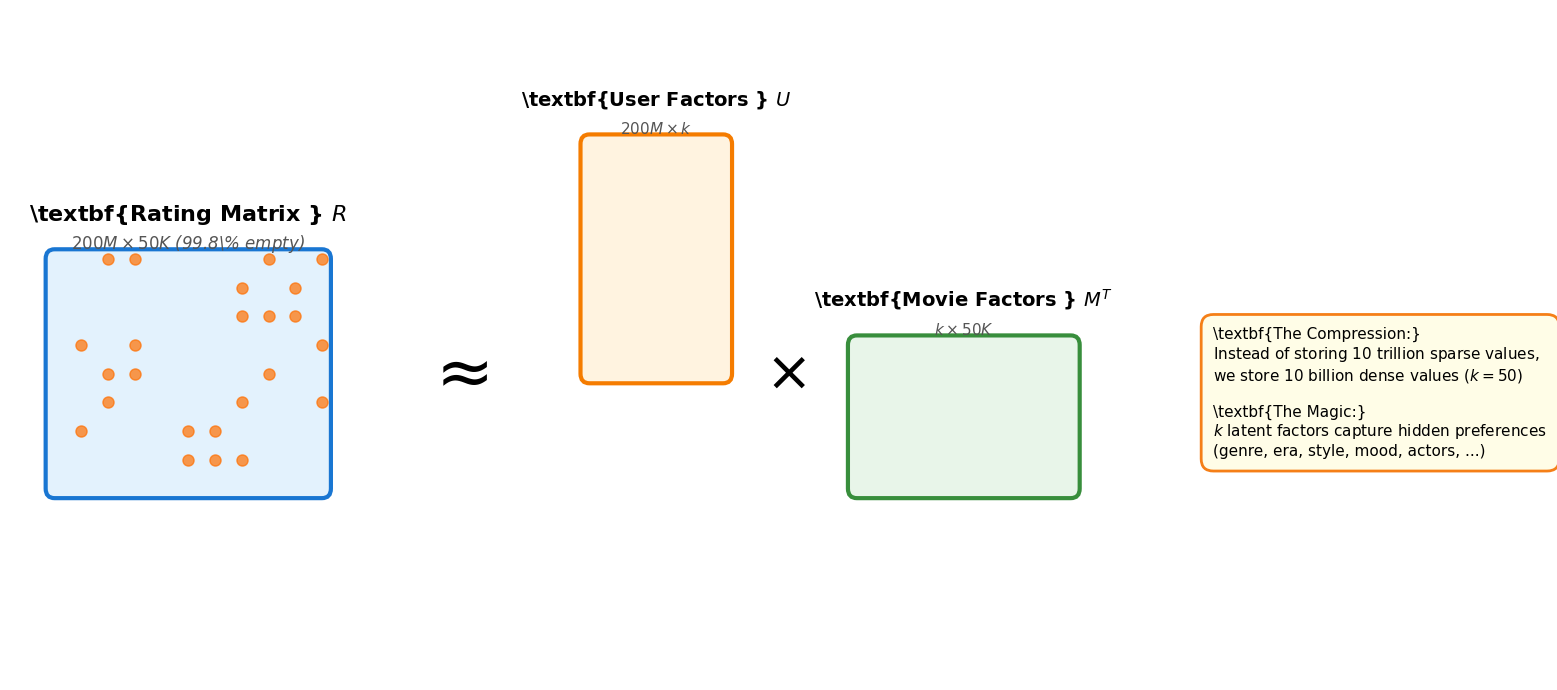

Imagine Netflix’s rating matrix:

Rows: 200 million users

Columns: 50,000 movies

Total cells: 10 trillion possible ratings

Actual ratings: ~20 billion (0.2% filled)

This matrix is 99.8% empty. But hidden in those sparse ratings are patterns: some users love action movies, others prefer documentaries, some movies appeal to specific demographics.

The ALS Solution: Matrix Factorization¶

ALS decomposes this giant sparse matrix into two smaller dense matrices:

Where:

: User-item rating matrix (200M × 50K)

: User factors (200M × )

: Movie factors (50K × )

: Number of latent factors (typically 10-50)

Source

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(16, 7))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.axis('off')

# Dimensions

users, movies = 8, 10

factors = 3

# Rating matrix (left)

rating_x, rating_y = 0.5, 2

rating_w, rating_h = 3, 2.4

rect_rating = FancyBboxPatch(

(rating_x, rating_y), rating_w, rating_h,

boxstyle="round,pad=0.1",

facecolor='#e3f2fd',

edgecolor='#1976d2',

linewidth=3

)

ax.add_patch(rect_rating)

# Add sparse pattern

np.random.seed(42)

sparse_mask = np.random.rand(users, movies) < 0.2

for i in range(users):

for j in range(movies):

if sparse_mask[i, j]:

x = rating_x + 0.3 + (j * rating_w / movies)

y = rating_y + 0.3 + (i * rating_h / users)

ax.plot(x, y, 'o', color='#ff6f00', markersize=8, alpha=0.7)

ax.text(rating_x + rating_w/2, rating_y + rating_h + 0.4,

r'\textbf{Rating Matrix } $R$',

ha='center', fontsize=16, weight='bold')

ax.text(rating_x + rating_w/2, rating_y + rating_h + 0.1,

r'$200M \times 50K$ (99.8\% empty)',

ha='center', fontsize=12, style='italic', color='#555')

# Approximately equals sign

ax.text(5, rating_y + rating_h/2, r'$\approx$',

ha='center', va='center', fontsize=50, weight='bold')

# User factors (right top)

user_x, user_y = 6.5, 3.2

user_w, user_h = 1.5, 2.4

rect_user = FancyBboxPatch(

(user_x, user_y), user_w, user_h,

boxstyle="round,pad=0.1",

facecolor='#fff3e0',

edgecolor='#f57c00',

linewidth=3

)

ax.add_patch(rect_user)

ax.text(user_x + user_w/2, user_y + user_h + 0.4,

r'\textbf{User Factors } $U$',

ha='center', fontsize=14, weight='bold')

ax.text(user_x + user_w/2, user_y + user_h + 0.1,

r'$200M \times k$',

ha='center', fontsize=11, style='italic', color='#555')

# Multiplication sign

ax.text(8.7, rating_y + rating_h/2, r'$\times$',

ha='center', va='center', fontsize=40, weight='bold')

# Movie factors (right bottom)

movie_x, movie_y = 9.5, 2

movie_w, movie_h = 2.4, 1.5

rect_movie = FancyBboxPatch(

(movie_x, movie_y), movie_w, movie_h,

boxstyle="round,pad=0.1",

facecolor='#e8f5e9',

edgecolor='#388e3c',

linewidth=3

)

ax.add_patch(rect_movie)

ax.text(movie_x + movie_w/2, movie_y + movie_h + 0.4,

r'\textbf{Movie Factors } $M^T$',

ha='center', fontsize=14, weight='bold')

ax.text(movie_x + movie_w/2, movie_y + movie_h + 0.1,

r'$k \times 50K$',

ha='center', fontsize=11, style='italic', color='#555')

# Explanatory box

explanation = (

r"\textbf{The Compression:}"

"\n"

r"Instead of storing $10$ trillion sparse values,"

"\n"

r"we store $10$ billion dense values ($k=50$)"

"\n\n"

r"\textbf{The Magic:}"

"\n"

r"$k$ latent factors capture hidden preferences"

"\n"

r"(genre, era, style, mood, actors, ...)"

)

ax.text(13.5, 3, explanation,

fontsize=11, ha='left', va='center',

bbox=dict(boxstyle='round,pad=0.8',

facecolor='#fffde7',

edgecolor='#f57f17',

linewidth=2))

ax.set_xlim(0, 16)

ax.set_ylim(0, 7)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

What Do These Latent Factors Mean?¶

The algorithm discovers patterns automatically. After training, we might find:

Factor 1: Action/adventure preference (high for Mad Max, low for Pride and Prejudice)

Factor 2: Serious vs. lighthearted (high for documentaries, low for comedies)

Factor 3: Classic vs. modern (high for Casablanca, low for recent releases)

Crucially: We never told the model “this is an action movie” or “this user likes comedies.” It learned these patterns from ratings alone.

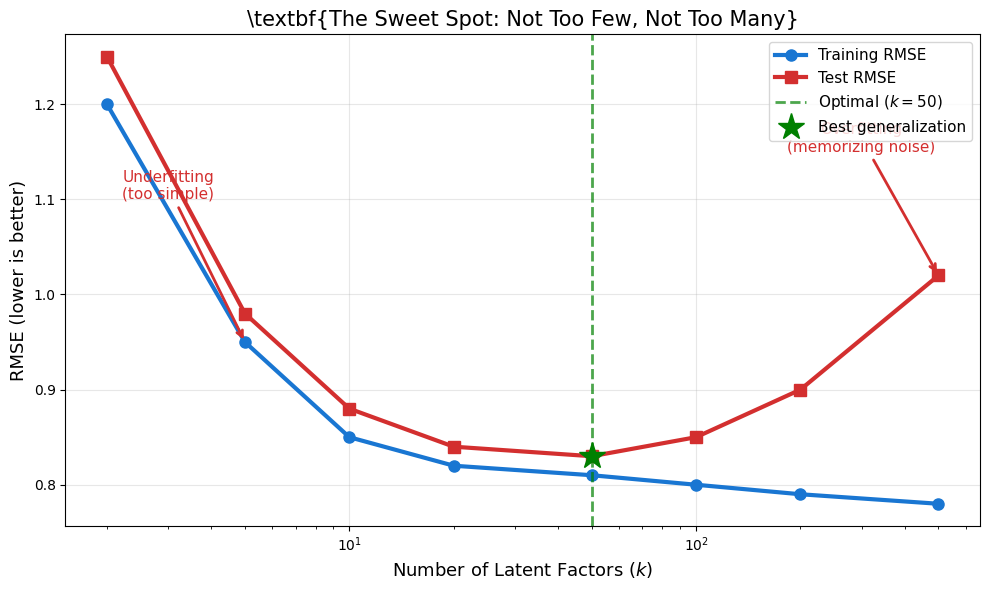

Why Fewer Dimensions Work Better¶

Source

# Simulate RMSE vs number of factors

factors_range = [2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, 500]

train_rmse = [1.2, 0.95, 0.85, 0.82, 0.81, 0.80, 0.79, 0.78]

test_rmse = [1.25, 0.98, 0.88, 0.84, 0.83, 0.85, 0.90, 1.02]

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

ax.plot(factors_range, train_rmse, 'o-', linewidth=3, markersize=8,

label='Training RMSE', color='#1976d2')

ax.plot(factors_range, test_rmse, 's-', linewidth=3, markersize=8,

label='Test RMSE', color='#d32f2f')

# Mark optimal point

optimal_idx = np.argmin(test_rmse)

ax.axvline(x=factors_range[optimal_idx], color='green', linestyle='--',

linewidth=2, alpha=0.7, label=f'Optimal ($k={factors_range[optimal_idx]}$)')

ax.plot(factors_range[optimal_idx], test_rmse[optimal_idx],

'g*', markersize=20, label='Best generalization')

ax.set_xlabel(r'Number of Latent Factors ($k$)', fontsize=13)

ax.set_ylabel(r'RMSE (lower is better)', fontsize=13)

ax.set_title(r'\textbf{The Sweet Spot: Not Too Few, Not Too Many}', fontsize=15)

ax.set_xscale('log')

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

ax.legend(fontsize=11, loc='upper right')

# Annotate regions

ax.annotate('Underfitting\n(too simple)', xy=(5, 0.95), xytext=(3, 1.1),

fontsize=11, ha='center', color='#d32f2f',

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle='->', color='#d32f2f', lw=2))

ax.annotate('Overfitting\n(memorizing noise)', xy=(500, 1.02), xytext=(300, 1.15),

fontsize=11, ha='center', color='#d32f2f',

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle='->', color='#d32f2f', lw=2))

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Why this happens:

Too few factors (): Can’t capture the complexity of human taste

Too many factors (): Starts memorizing individual ratings instead of learning patterns

Just right (): Captures real patterns while ignoring noise

Part 3: Example 2 - Multi-Head Attention in Transformers¶

The Problem: Understanding Language¶

Consider the sentence:

“The bank by the river was steep, but the bank downtown was closed.”

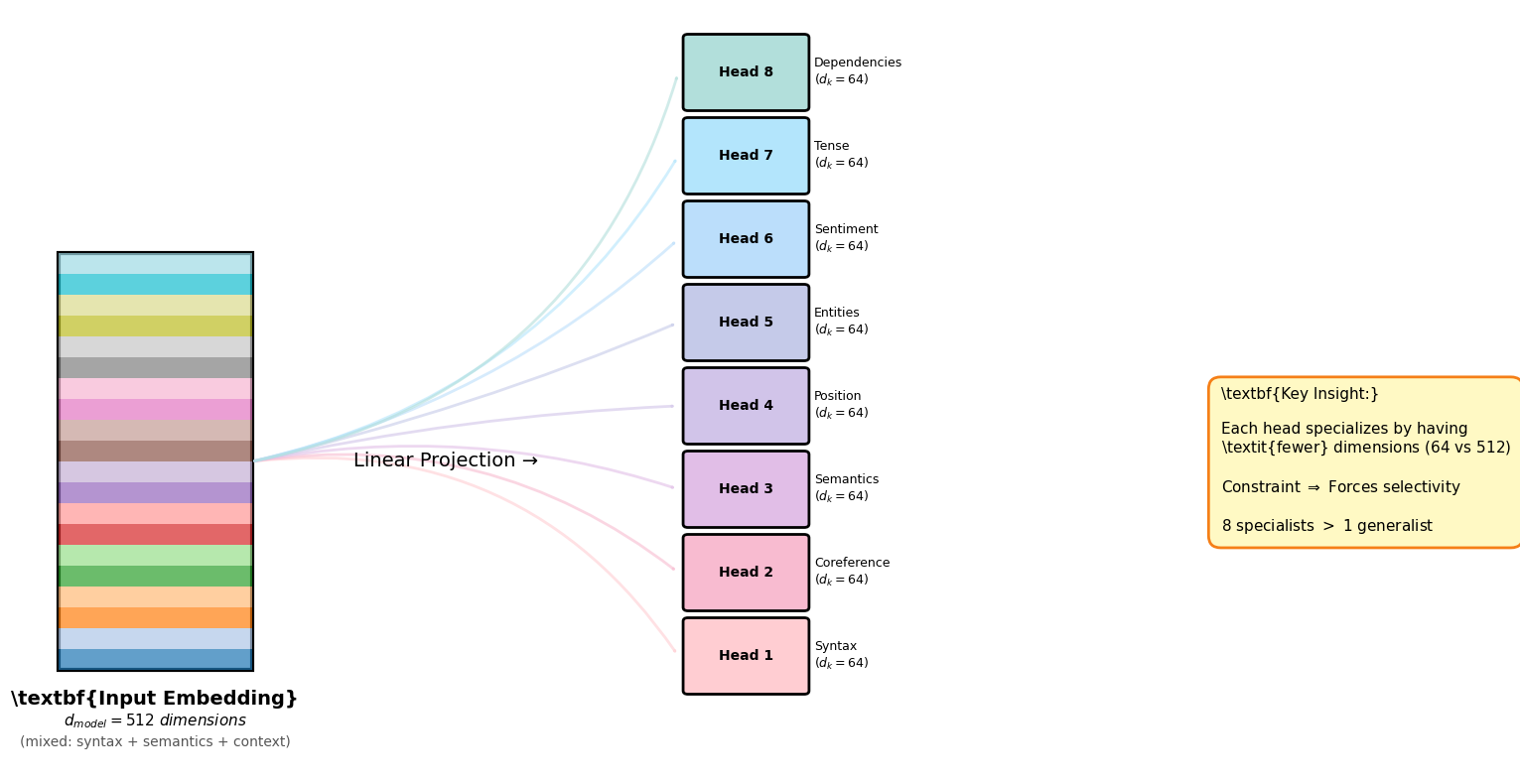

The word “bank” means different things based on context. A single 512-dimensional embedding must somehow encode:

Syntactic role (noun)

Semantic meaning (financial institution OR riverbank)

Relationships (to “river” vs. “downtown”)

The Multi-Head Solution: Parallel Subspaces¶

Instead of using one 512-dimensional attention mechanism, transformers use 8 parallel 64-dimensional mechanisms (called “heads”).

Source

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(16, 8))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.axis('off')

# Input embedding

input_x, input_y = 0.5, 1.5

input_w, input_h = 2, 6

rect_input = Rectangle((input_x, input_y), input_w, input_h,

facecolor='none', edgecolor='black', linewidth=3)

ax.add_patch(rect_input)

# Fill with colorful segments

num_segments = 20

colors = plt.cm.tab20.colors

for i in range(num_segments):

seg_h = input_h / num_segments

rect_seg = Rectangle((input_x, input_y + i*seg_h), input_w, seg_h,

facecolor=colors[i % len(colors)], alpha=0.7, edgecolor='none')

ax.add_patch(rect_seg)

ax.text(input_x + input_w/2, input_y - 0.5,

r'\textbf{Input Embedding}',

ha='center', fontsize=14, weight='bold')

ax.text(input_x + input_w/2, input_y - 0.8,

r'$d_{model} = 512$ dimensions',

ha='center', fontsize=11, style='italic')

ax.text(input_x + input_w/2, input_y - 1.1,

r'(mixed: syntax + semantics + context)',

ha='center', fontsize=10, color='#555')

# Arrow and projection

ax.text(4.5, 4.5, "Linear Projection →",

ha='center', va='center', fontsize=14)

# Output heads

head_x = 7

head_spacing = 1.2

head_w = 1.2

head_h = 1

colors_heads = ['#ffcdd2', '#f8bbd0', '#e1bee7', '#d1c4e9',

'#c5cae9', '#bbdefb', '#b3e5fc', '#b2dfdb']

head_labels = ['Syntax', 'Coreference', 'Semantics', 'Position',

'Entities', 'Sentiment', 'Tense', 'Dependencies']

for i in range(8):

y_pos = 1.2 + i * head_spacing

# Head box

rect_head = FancyBboxPatch(

(head_x, y_pos), head_w, head_h,

boxstyle="round,pad=0.05",

facecolor=colors_heads[i],

edgecolor='black',

linewidth=2

)

ax.add_patch(rect_head)

# Head label

ax.text(head_x + head_w/2, y_pos + head_h/2,

f'Head {i+1}',

ha='center', va='center', fontsize=10, weight='bold')

# Dimension label

ax.text(head_x + head_w + 0.1, y_pos + head_h/2,

f'{head_labels[i]}\n($d_k=64$)',

ha='left', va='center', fontsize=9)

# Arrow from input to head

arrow = FancyArrowPatch(

(input_x + input_w, input_y + input_h/2),

(head_x - 0.1, y_pos + head_h/2),

arrowstyle='-|>',

connectionstyle=f'arc3,rad={0.3*(i-3.5)/3.5}',

color=colors_heads[i],

linewidth=2,

alpha=0.6,

zorder=1

)

ax.add_patch(arrow)

# Explanation box

explanation = (

r"\textbf{Key Insight:}"

"\n\n"

r"Each head specializes by having"

"\n"

r"\textit{fewer} dimensions ($64$ vs $512$)"

"\n\n"

r"Constraint $\Rightarrow$ Forces selectivity"

"\n\n"

r"8 specialists $>$ 1 generalist"

)

ax.text(12.5, 4.5, explanation,

fontsize=11, ha='left', va='center',

bbox=dict(boxstyle='round,pad=0.8',

facecolor='#fff9c4',

edgecolor='#f57f17',

linewidth=2))

ax.set_xlim(0, 15)

ax.set_ylim(0, 11)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

What Do These Heads Learn?¶

Research analyzing trained transformers found heads specializing in:

Syntactic heads: Track subject-verb agreement, noun-adjective relationships

Positional heads: Attend to previous/next tokens

Semantic heads: Link pronouns to their referents (“it” → “bank”)

Rare word heads: Focus on low-frequency vocabulary

Again, these roles emerge from training—we never explicitly told heads what to focus on.

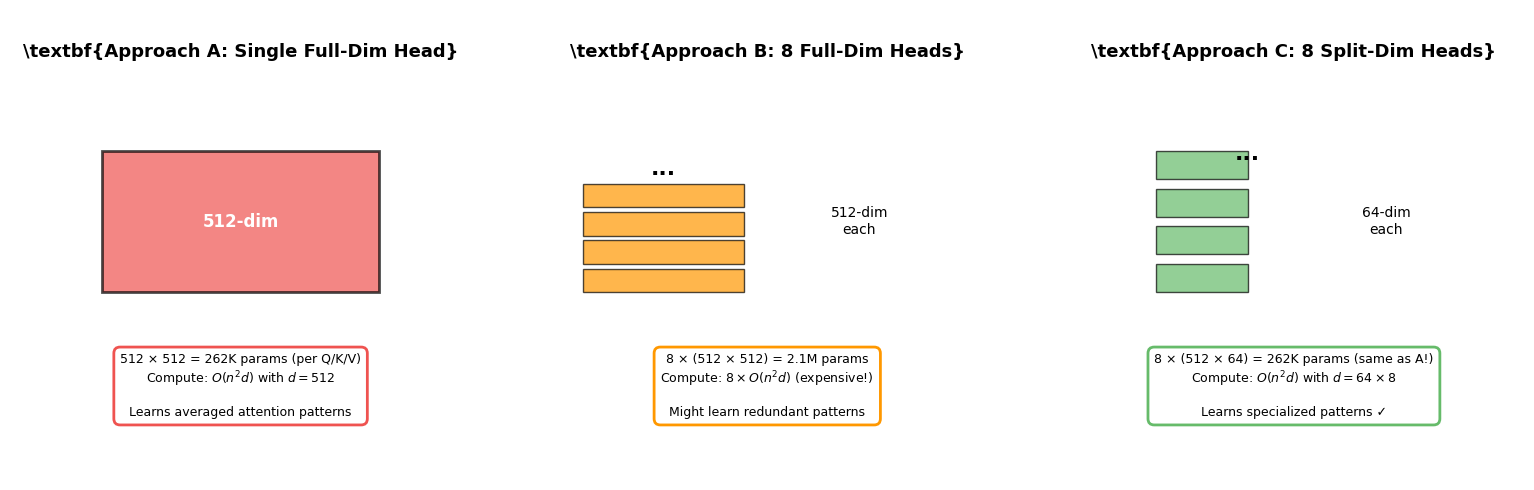

Why Multiple Lower-Dimensional Heads?¶

Let’s compare three approaches:

Source

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 3, figsize=(16, 5))

approaches = [

{

'title': r'\textbf{Approach A: Single Full-Dim Head}',

'config': '1 head × 512 dims',

'params': '512 × 512 = 262K params (per Q/K/V)',

'cost': 'Compute: $O(n^2 d)$ with $d=512$',

'quality': 'Learns averaged attention patterns',

'color': '#ef5350'

},

{

'title': r'\textbf{Approach B: 8 Full-Dim Heads}',

'config': '8 heads × 512 dims each',

'params': '8 × (512 × 512) = 2.1M params',

'cost': 'Compute: $8 \\times O(n^2 d)$ (expensive!)',

'quality': 'Might learn redundant patterns',

'color': '#ff9800'

},

{

'title': r'\textbf{Approach C: 8 Split-Dim Heads}',

'config': '8 heads × 64 dims each',

'params': '8 × (512 × 64) = 262K params (same as A!)',

'cost': 'Compute: $O(n^2 d)$ with $d=64 \\times 8$',

'quality': 'Learns specialized patterns ✓',

'color': '#66bb6a'

}

]

for ax, approach in zip(axes, approaches):

ax.set_xlim(0, 10)

ax.set_ylim(0, 10)

ax.axis('off')

# Title

ax.text(5, 9, approach['title'], ha='center', fontsize=13, weight='bold')

# Visual representation

if approach['config'].startswith('1 head'):

# Single large box

rect = Rectangle((2, 4), 6, 3, facecolor=approach['color'],

edgecolor='black', linewidth=2, alpha=0.7)

ax.add_patch(rect)

ax.text(5, 5.5, '512-dim', ha='center', va='center',

fontsize=12, weight='bold', color='white')

elif approach['config'].startswith('8 heads × 512'):

# 8 large boxes stacked

for i in range(4):

rect = Rectangle((1, 4 + i*0.6), 3.5, 0.5,

facecolor=approach['color'],

edgecolor='black', linewidth=1, alpha=0.7)

ax.add_patch(rect)

ax.text(2.75, 6.5, '...', ha='center', fontsize=16, weight='bold')

ax.text(7, 5.5, '512-dim\neach', ha='center', va='center', fontsize=10)

else:

# 8 small boxes

for i in range(4):

rect = Rectangle((2, 4 + i*0.8), 2, 0.6,

facecolor=approach['color'],

edgecolor='black', linewidth=1, alpha=0.7)

ax.add_patch(rect)

ax.text(4, 6.8, '...', ha='center', fontsize=16, weight='bold')

ax.text(7, 5.5, '64-dim\neach', ha='center', va='center', fontsize=10)

# Details

details = f"{approach['params']}\n{approach['cost']}\n\n{approach['quality']}"

ax.text(5, 2, details, ha='center', va='center', fontsize=9,

bbox=dict(boxstyle='round,pad=0.5', facecolor='white',

edgecolor=approach['color'], linewidth=2))

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Approach C wins because:

Same parameter count as single-head (no extra memory)

Similar computational cost (parallelizes well on GPUs)

Better quality through specialization

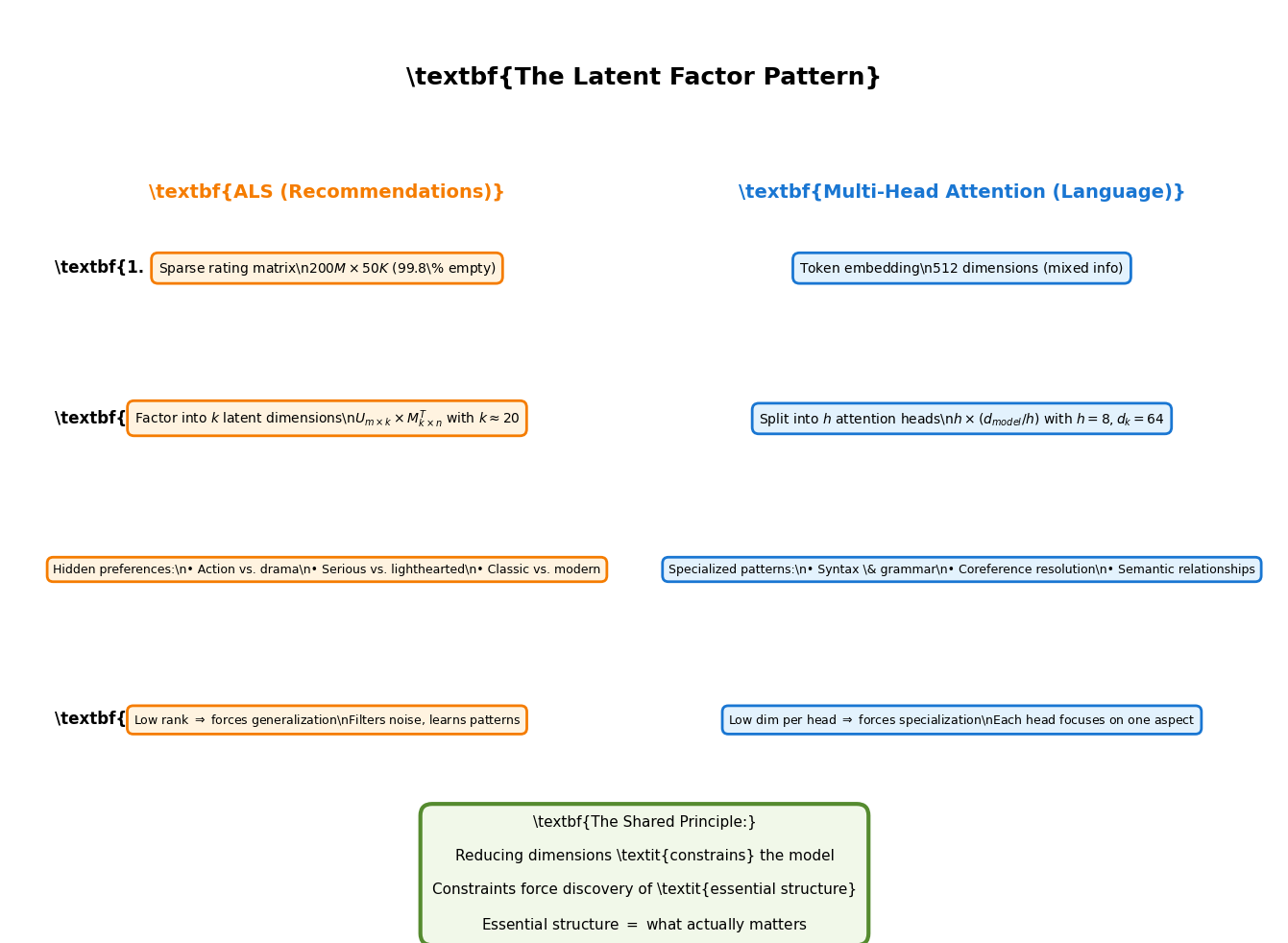

Part 4: The Deep Connection¶

What ALS and Multi-Head Attention Share¶

Both techniques follow the same fundamental pattern:

Source

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(14, 10))

ax.axis('off')

ax.set_xlim(0, 14)

ax.set_ylim(0, 12)

# Title

ax.text(7, 11, r'\textbf{The Latent Factor Pattern}',

ha='center', fontsize=18, weight='bold')

# Column headers

ax.text(3.5, 9.5, r'\textbf{ALS (Recommendations)}',

ha='center', fontsize=14, weight='bold', color='#f57c00')

ax.text(10.5, 9.5, r'\textbf{Multi-Head Attention (Language)}',

ha='center', fontsize=14, weight='bold', color='#1976d2')

# Row 1: High-dimensional input

y_pos = 8.5

ax.text(0.5, y_pos, r'\textbf{1. Start}', ha='left', fontsize=12, weight='bold')

ax.text(3.5, y_pos,

r'Sparse rating matrix\n$200M \times 50K$ (99.8\% empty)',

ha='center', fontsize=10,

bbox=dict(boxstyle='round,pad=0.5', facecolor='#fff3e0', edgecolor='#f57c00', linewidth=2))

ax.text(10.5, y_pos,

r'Token embedding\n$512$ dimensions (mixed info)',

ha='center', fontsize=10,

bbox=dict(boxstyle='round,pad=0.5', facecolor='#e3f2fd', edgecolor='#1976d2', linewidth=2))

# Row 2: Decomposition

y_pos = 6.5

ax.text(0.5, y_pos, r'\textbf{2. Decompose}', ha='left', fontsize=12, weight='bold')

ax.text(3.5, y_pos,

r'Factor into $k$ latent dimensions\n$U_{m \times k} \times M_{k \times n}^T$ with $k \approx 20$',

ha='center', fontsize=10,

bbox=dict(boxstyle='round,pad=0.5', facecolor='#fff3e0', edgecolor='#f57c00', linewidth=2))

ax.text(10.5, y_pos,

r'Split into $h$ attention heads\n$h \times (d_{model}/h)$ with $h=8, d_k=64$',

ha='center', fontsize=10,

bbox=dict(boxstyle='round,pad=0.5', facecolor='#e3f2fd', edgecolor='#1976d2', linewidth=2))

# Row 3: What gets learned

y_pos = 4.5

ax.text(0.5, y_pos, r'\textbf{3. Discover}', ha='left', fontsize=12, weight='bold')

ax.text(3.5, y_pos,

r'Hidden preferences:\n• Action vs. drama\n• Serious vs. lighthearted\n• Classic vs. modern',

ha='center', fontsize=9,

bbox=dict(boxstyle='round,pad=0.5', facecolor='#fff3e0', edgecolor='#f57c00', linewidth=2))

ax.text(10.5, y_pos,

r'Specialized patterns:\n• Syntax \& grammar\n• Coreference resolution\n• Semantic relationships',

ha='center', fontsize=9,

bbox=dict(boxstyle='round,pad=0.5', facecolor='#e3f2fd', edgecolor='#1976d2', linewidth=2))

# Row 4: Why it works

y_pos = 2.5

ax.text(0.5, y_pos, r'\textbf{4. Why}', ha='left', fontsize=12, weight='bold')

ax.text(3.5, y_pos,

r'Low rank $\Rightarrow$ forces generalization\nFilters noise, learns patterns',

ha='center', fontsize=9,

bbox=dict(boxstyle='round,pad=0.5', facecolor='#fff3e0', edgecolor='#f57c00', linewidth=2))

ax.text(10.5, y_pos,

r'Low dim per head $\Rightarrow$ forces specialization\nEach head focuses on one aspect',

ha='center', fontsize=9,

bbox=dict(boxstyle='round,pad=0.5', facecolor='#e3f2fd', edgecolor='#1976d2', linewidth=2))

# Central insight box

insight = (

r"\textbf{The Shared Principle:}"

"\n\n"

r"Reducing dimensions \textit{constrains} the model"

"\n\n"

r"Constraints force discovery of \textit{essential structure}"

"\n\n"

r"Essential structure $=$ what actually matters"

)

ax.text(7, 0.5, insight,

ha='center', va='center', fontsize=11,

bbox=dict(boxstyle='round,pad=0.8', facecolor='#f1f8e9',

edgecolor='#558b2f', linewidth=3))

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

The Mathematical Connection¶

Both use the same core trick: low-rank approximation.

ALS: Approximate rank- matrix with rank- factorization ()

Multi-Head Attention: Instead of one -dimensional space, use subspaces of dimension

Both work because:

Real patterns are low-dimensional: Human preferences and language structure don’t need millions of dimensions

Constraints prevent overfitting: Fewer dimensions = can’t memorize noise

Specialization emerges naturally: Multiple subspaces learn different aspects

Part 5: When to Use This Pattern¶

The Decision Framework¶

Use dimensionality reduction when:

✅ Data has hidden structure: Relationships between features exist but aren’t explicit ✅ High sparsity: Most feature combinations never occur ✅ Need generalization: Want to predict unseen combinations ✅ Interpretability matters: Want to understand what the model learned

Avoid when:

❌ Every dimension is meaningful: No redundancy in features ❌ Dense data: All combinations are observed ❌ Exact reconstruction needed: Can’t afford any approximation error

Practical Guidelines¶

For recommendation systems:

Start with , increase until test error plateaus

Typical range: 10-50 factors for most datasets

More factors needed for large catalogs (millions of items)

For transformers:

Standard: 8-16 heads with

Smaller models (BERT-base): 12 heads,

Larger models (GPT-3): 96 heads,

Keep between 32-128 for best results

Summary¶

The latent factor principle appears across machine learning because it captures a fundamental truth: real-world complexity often has simple underlying structure.

Key Takeaways¶

Reducing dimensions ≠ losing information when most “dimensions” are noise or redundancy

Constraints enable discovery: Forcing models into lower dimensions makes them learn what truly matters

Specialization through separation: Multiple small subspaces often outperform one large space

Patterns emerge, not assigned: In both ALS and multi-head attention, roles are learned through training, not programmed

Universal applicability: This pattern works for recommendations, language, images, graphs, and more

The Deeper Lesson¶

When you encounter a high-dimensional problem, your first instinct might be to preserve all dimensions. But often, the right move is counterintuitive: compress first, then learn.

The magic happens in the compression. By forcing information through a bottleneck, you filter out noise and surface the essential patterns that actually matter.

Further Reading¶

ALS and Matrix Factorization:

ALS Tutorial - Full implementation with MovieLens data

Netflix Prize papers: Original work on collaborative filtering

Implicit feedback ALS for binary data (clicks, views)

Multi-Head Attention:

L04 - Multi-Head Attention - Deep dive into transformer attention

“Attention Is All You Need” (Vaswani et al., 2017)

BERTology research analyzing what attention heads learn

Related Concepts:

Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Linear dimensionality reduction

Autoencoders: Neural network approach to compression

Low-rank tensor decomposition: Extends to higher dimensions

This post demonstrates a general principle. The specific implementations depend on your domain, data size, and computational constraints. Always validate dimensionality choices on held-out test data.