A visual guide to Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) and the bridge from text to tensors

In this series, we are building a Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT) from scratch—the exact architecture behind systems like ChatGPT and Llama.

But before we can build the brain (the Transformer), we need to teach it to read. A Transformer generally doesn’t understand letters or words; it understands numbers. To bridge this gap, we need a “translator” that converts human text into a sequence of integers.

This process is called Tokenization. It is the very first step in the pipeline.

By the end of this post, you’ll understand:

Why we don’t just use characters or whole words.

The intuition behind Byte Pair Encoding (BPE).

How to build a BPE tokenizer from scratch that handles “Out of Vocabulary” words.

Part 1: The Goldilocks Problem¶

To turn text into numbers, we have three choices. Each has a major flaw:

| Method | Example | Vocab Size | Problem |

|---|---|---|---|

| Character-level | c, a, t | Tiny (~100) | Characters have no meaning. Sequences get too long. |

| Word-level | cat | Massive (50k+) | Can’t handle “cats” if it only saw “cat”. Vocabulary explosion: “play”, “plays”, “played”, “playing” = 4 separate entries. |

| Subword-level | play, ##ing | Medium (32k-50k) | Just right. Meaningful and flexible. “play” + “##ing” = just 2 tokens for all variants. |

Subword tokenization (specifically BPE) is the industry standard used by almost every modern Large Language Model (GPT-4, Llama 3, Claude). It strikes the perfect balance:

It keeps common words (like “apple”) as single integers for efficiency.

It breaks rare words (like “unbelievable”) into meaningful chunks (

un,believ,able) so the model can understand words it has never seen before.

Part 2: Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) Intuition¶

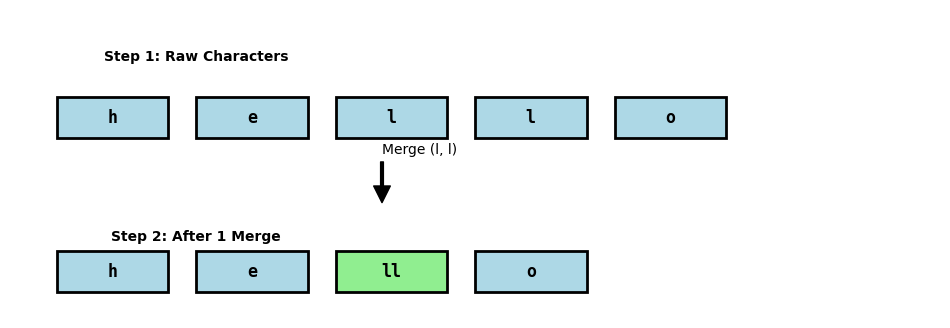

BPE is an iterative algorithm. It starts with a vocabulary of individual characters and slowly “glues” the most frequent adjacent pairs together to create new tokens.

The Algorithm¶

Initialize: Break words in your training data into character sequences.

Count: Find the most frequent pair of adjacent tokens (e.g.,

tandh).Merge: Create a new token

thand replace all occurrences in the data.Repeat: Stop when you reach a target vocabulary size.

Let’s visualize this “gluing” process:

Part 3: Coding a Tiny BPE Tokenizer (End-to-End)¶

Real production tokenizers have lots of details (bytes, whitespace markers, Unicode edge cases, normalization, special tokens, etc.).

Here we’ll build a tiny BPE that still captures the core idea:

Learn merges from a toy corpus

Tokenize new words by repeatedly applying those merges

Avoid “out of vocabulary” failures by falling back to smaller pieces

3.1 Training data¶

We’ll represent training text as a dictionary: word → frequency.

Why these particular words?

This toy corpus is deliberately small, but it’s designed to force the BPE learner to discover a few useful subword patterns:

High-frequency “everyday” words (

the,fox)

These simulate common tokens that real tokenizers usually keep as single units.Plural / suffix patterns (

foxes,boxes,wishes)

These share common endings likees/s/sh+es. By including several words with the same suffix, we increase the chance BPE learns merges that create reusable “ending” tokens (e.g.es).Prefix + root + suffix morphology (

un,able,unable,believe,believable,unbelievable)

This set encourages the tokenizer to learn pieces that behave like morphemes:prefix:

unsuffix:

ablea recurring stem-ish chunk around

believ...

The key idea: BPE doesn’t “understand” grammar — it only merges frequent adjacent pairs.

So we choose words that repeat the same adjacent patterns (like u→n, or a→b→l→e) across multiple items, making those merges statistically likely.

toy_word_counts = {

# common

"the": 50,

"fox": 30,

# plural patterns (to encourage "es")

"foxes": 5,

"boxes": 12,

"wishes": 8,

# morpheme-ish patterns (to encourage "un" and "able")

"un": 20,

"able": 25,

"unable": 12,

# "believ" appears inside believable/unbelievable (note: no second 'e' here)

"believe": 18,

"believer": 6,

"believable": 8,

"unbelievable": 3,

}

toy_word_counts{'the': 50,

'fox': 30,

'foxes': 5,

'boxes': 12,

'wishes': 8,

'un': 20,

'able': 25,

'unable': 12,

'believe': 18,

'believer': 6,

'believable': 8,

'unbelievable': 3}3.2 The BPE training loop¶

We store each word as a space-delimited sequence of symbols (initially characters). Then we repeatedly:

count the most frequent adjacent pair

merge it everywhere

record that merge rule

def build_vocab(word_counts: dict[str, int]) -> dict[str, int]:

"""Convert {"word": freq} into {"c h a r s": freq}."""

return {" ".join(list(word)): freq for word, freq in word_counts.items()}

def get_stats(vocab: dict[str, int]) -> dict[tuple[str, str], int]:

"""Count adjacent pair frequencies across the vocab, weighted by word frequency."""

pairs = defaultdict(int)

for word, freq in vocab.items():

symbols = word.split()

for i in range(len(symbols) - 1):

pairs[(symbols[i], symbols[i + 1])] += freq

return pairs

def merge_word(symbols: list[str], pair: tuple[str, str]) -> list[str]:

"""Merge all occurrences of (a, b) into 'ab' within a single token list."""

a, b = pair

merged = []

i = 0

while i < len(symbols):

if i < len(symbols) - 1 and symbols[i] == a and symbols[i + 1] == b:

merged.append(a + b)

i += 2

else:

merged.append(symbols[i])

i += 1

return merged

def merge_vocab(pair: tuple[str, str], v_in: dict[str, int]) -> dict[str, int]:

"""Apply one merge rule to every word in the vocab."""

v_out = {}

for word, freq in v_in.items():

symbols = word.split()

new_symbols = merge_word(symbols, pair)

v_out[" ".join(new_symbols)] = freq

return v_out

def train_bpe(word_counts: dict[str, int], num_merges: int = 16) -> tuple[list[tuple[str, str]], dict[str, int]]:

"""Learn `num_merges` merge rules from a corpus.

Returns:

merges: List of merge pairs in the order learned.

vocab: Final merged vocabulary representation (space-delimited token strings -> freq).

"""

vocab = build_vocab(word_counts)

merges: list[tuple[str, str]] = []

for _ in range(num_merges):

stats = get_stats(vocab)

if not stats:

break

best_pair = max(stats, key=stats.get)

merges.append(best_pair)

vocab = merge_vocab(best_pair, vocab)

return merges, vocab

merges, trained_vocab = train_bpe(toy_word_counts, num_merges=16)

# Show the merge rules we learned

for i, m in enumerate(merges):

print(f"{i:02d}: {m[0]} + {m[1]} -> {m[0] + m[1]}")00: h + e -> he

01: t + he -> the

02: a + b -> ab

03: ab + l -> abl

04: abl + e -> able

05: o + x -> ox

06: f + ox -> fox

07: u + n -> un

08: b + e -> be

09: be + l -> bel

10: bel + i -> beli

11: beli + e -> belie

12: belie + v -> believ

13: believ + e -> believe

14: e + s -> es

15: b + ox -> box

3.3 Tokenizing new words (including Out-of-Vocabulary words)¶

Tokenization = start from characters, then apply merges in the same order we learned them.

def bpe_tokenize(word: str, merges: list[tuple[str, str]]) -> list[str]:

"""Apply BPE merges to a single word."""

tokens = list(word)

for pair in merges:

tokens = merge_word(tokens, pair)

return tokens

test_words = [

"the",

"unbelievable",

"believable",

"unable",

"foxes",

"unbelievably", # not in our toy corpus -> still tokenizes

]

for w in test_words:

print(f"{w:14s} -> {bpe_tokenize(w, merges)}")the -> ['the']

unbelievable -> ['un', 'believ', 'able']

believable -> ['believ', 'able']

unable -> ['un', 'able']

foxes -> ['fox', 'es']

unbelievably -> ['un', 'believ', 'abl', 'y']

Notice what happened to unbelievably: we didn’t need it in the training vocab.

The tokenizer falls back to smaller pieces automatically.

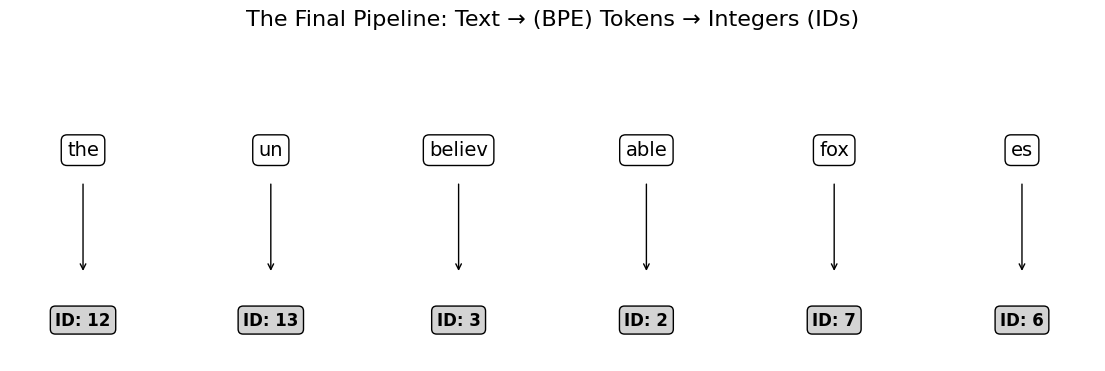

Part 4: The Tokenization Pipeline (Text → Tokens → IDs)¶

Once we have merges, we can build a vocabulary: the set of tokens our tokenizer can produce on this corpus. Then we assign each token a unique integer ID.

This list of integers (ids) is the actual input to our GPT. When we build the training loop in [L08_Training_the_LLM.md, we won’t be feeding it English sentences; we will be feeding it these exact lists of numbers.

In the next blog, we will see how the model turns these simple integers into rich, high-dimensional vectors.

def build_token2id(vocab: dict[str, int], special_tokens: list[str] | None = None) -> dict[str, int]:

"""Build a stable token -> ID mapping from the trained vocab."""

token_set = set()

for word in vocab.keys():

token_set.update(word.split())

special_tokens = special_tokens or ["<pad>", "<unk>"]

tokens_sorted = sorted(token_set)

all_tokens = special_tokens + tokens_sorted

return {tok: i for i, tok in enumerate(all_tokens)}

token2id = build_token2id(trained_vocab)

# A sentence that very clearly goes through BPE

sentence = "The unbelievable foxes"

words = sentence.lower().split()

tokens = []

for w in words:

tokens.extend(bpe_tokenize(w, merges))

ids = [token2id.get(t, token2id["<unk>"]) for t in tokens]

print("Sentence:", sentence)

print("Tokens :", tokens)

print("IDs :", ids)Sentence: The unbelievable foxes

Tokens : ['the', 'un', 'believ', 'able', 'fox', 'es']

IDs : [12, 13, 3, 2, 7, 6]

Visualizing: the final bridge into integers¶

(Note: real tokenizers also encode spaces/punctuation carefully — this is the clean “words only” version.)

Part 5: Special Tokens - The Control Signals¶

Production tokenizers include special tokens that aren’t regular words but serve as control signals for the model:

| Token | Purpose | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

<pad> | Padding | Fill shorter sequences to match batch size |

<unk> | Unknown | Fallback for truly unknown tokens (rare in BPE) |

| `< | endoftext | >` |

| `< | im_start | >, < |

These tokens are added to the vocabulary before training begins and are never broken down into smaller pieces. They act like “keywords” that tell the model about document structure and conversation flow.

Why they matter: When fine-tuning for chat (as we’ll see in L10), the model learns to generate <|im_end|> when it’s done responding, telling the system to stop generating and return control to the user.

Summary¶

We have successfully bridged the gap between human language and machine numbers:

The Goal: To build a GPT, we first need to convert text into numbers.

BPE: We use Byte Pair Encoding to learn a “gluing” recipe that efficiently compresses text into useful subwords.

Robustness: This method ensures our model never crashes on unknown words—it just breaks them down into smaller, known pieces.

Next Step: We now have our Token IDs. In the next lesson, we will give these numbers meaning.

Next Up: L02 – Embeddings & Positional Encoding.

Now that we have IDs, how do we turn them into high-dimensional vectors that capture “meaning”? And how do we tell the model that “The cat ate the mouse” is different from “The mouse ate the cat”?