How words become vectors in space, and how we tell time without a clock

In L01 - Tokenization, we turned text into IDs. But to a neural network, ID 464 and ID 465 are just arbitrary numbers. There is no inherent relationship between them.

In this post, we solve two problems:

Meaning: How do we represent words so that “King” is mathematically closer to “Queen” than it is to “Toaster”?

Order: Since the attention-based model we’ll build in the next lesson processes all tokens at once, how do we tell it that “The dog bit the man” is different from “The man bit the dog”?

By the end of this post, you’ll understand:

The intuition of Embedding Spaces.

How to implement a lookup table from scratch.

The beautiful math behind Sinusoidal Positional Encodings.

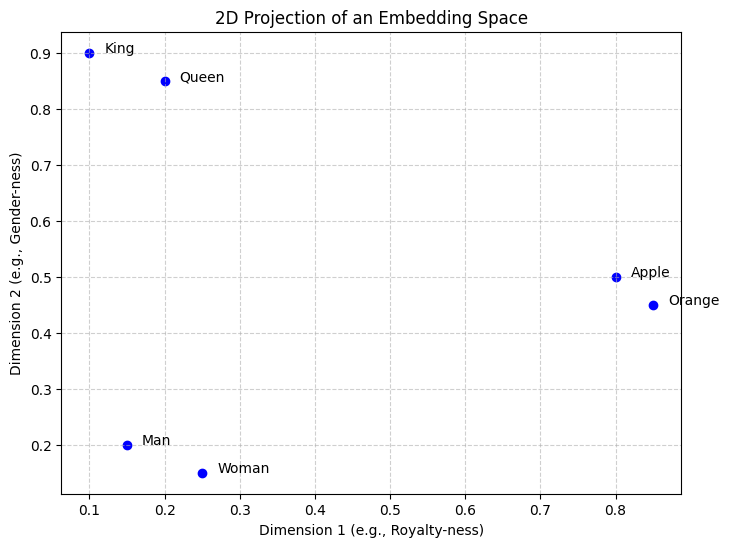

Part 1: The Embedding Space¶

Imagine every word is a point in a high-dimensional room. Words with similar meanings are “clumped” together. This is an Embedding Space.

An Embedding Layer is simply a big lookup table. If our vocabulary size is 10,000 and we want each word to be represented by a vector of 512 numbers, our table is a matrix.

The Lookup Operation¶

When the model sees ID 5, it doesn’t do math on the number 5. It simply grabs the 5th row of the embedding matrix.

Part 2: The Problem of Order¶

Standard Neural Networks (like the MLPs we built in the Neural Networks from Scratch series) process data in a specific order. The attention mechanism we’ll introduce next is parallel. It looks at every word in a sentence at the exact same time.

Without help, the attention-based model sees the sentence “The dog bit the man” as a bag of words. It has no idea which word came first.

We fix this by adding Positional Encodings.

Part 3: Positional Encoding (The Sine/Cosine Trick)¶

This is often the most confusing part of the Transformer architecture, so let’s derive it from scratch.

The Problem: Why not just count?¶

If we want to represent the order of words, the simplest idea is to just assign an integer to each position:

“The” 1

“Dog” 2

“Bit” 3

Why this fails:

Exploding Values: For a long document, the 5,000th word would have the value 5000. Neural networks hate large, unbounded numbers; they cause gradients to explode and training to become unstable.

Inconsistent Steps (if normalized): You might try dividing by the total length (e.g., for a 3-word sentence). But then the “time distance” between words changes depending on the sentence length. We need a method where the step size is bounded and consistent.

The Intuition: The “Binary Clock”¶

So, how do we represent numbers that get bigger and bigger without using huge values? We use patterns. Think of how binary numbers work.

Let’s start with a simple 3-bit binary counter to see the pattern clearly:

| Position | Bit 2 (Slow) | Bit 1 (Medium) | Bit 0 (Fast) | Binary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 000 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 001 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 010 |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 011 |

| 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 101 |

| 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 110 |

| 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 111 |

Notice the pattern?

Bit 0 (Fast) alternates every single step: (High Frequency).

Bit 1 (Medium) alternates every two steps: (Lower Frequency).

Bit 2 (Slow) alternates every four steps: (Lowest Frequency).

Each column oscillates at a different frequency. Together, they create a unique combination for every row, using only 0s and 1s.

From Binary to Continuous (The Spectrum)¶

Transformers adapt this binary idea using continuous waves (Sine and Cosine). But instead of just “fast” and “slow,” we have a smooth spectrum of frequencies across the embedding dimensions.

Dimension 0 (The Seconds Hand): The wave wiggles extremely fast. A small change in position causes a huge change in value. This gives the model precision (distinguishing word #5 from #6).

Dimension 100...: The frequency gradually slows down.

Dimension 512 (The Hour Hand): The wave wiggles extremely slowly. This gives the model long-term context (distinguishing word #5 from #5000).

The Formula¶

For a position and dimension index :

Even dimensions () use Sine.

Odd dimensions () use Cosine.

Don’t let the 10000... term scare you. It is just a “wavelength knob.” Let’s plug in some real numbers to see it in action.

Example: Plugging in the Numbers

Imagine we have a model with . This means we have 256 pairs of Sine/Cosine waves.

Case 1: The “Fast” Pair (Dimensions 0 & 1) We are at the start of the vector ().

Dim 0: Wiggles every ~6 words.

Dim 1: Same speed, just shifted.

This pair acts like the “Seconds Hand” (High Precision).

Case 2: The “Slow” Pair (Dimensions 510 & 511) We are at the end of the vector ().

Dim 510:

Dim 511:

This pair acts like the “Hour Hand” (Long-term Context). It takes ~62,800 words to complete one cycle!

Visualization¶

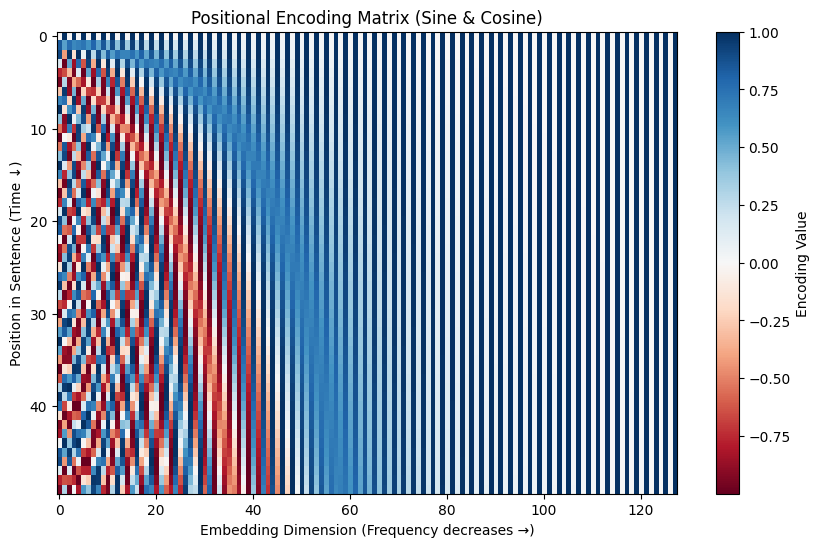

Let’s generate the matrix. In the plot below:

X-axis: The Embedding Dimensions (0 to 128).

Y-axis: The Position in the sentence (0 to 50).

Color: The value (Blue is negative, Red is positive).

Notice the “barber pole” pattern? That is the frequencies getting slower as you move to the right (higher dimensions).

Part 4: Putting it Together¶

The final input to our model is:

Now, the vector for “dog” at position 2 is slightly different from the vector for “dog” at position 5. The “meaning” is the same, but the “stamp” of its location is unique.

# Pseudo-code for the input pipeline

word_ids = [464, 2068, 7586] # "The quick brown"

embeddings = embedding_layer(word_ids) # Shape: [3, 512]

positions = positional_encoding_layer(range(len(word_ids))) # Shape: [3, 512]

final_input = embeddings + positions

Concrete Example: What the Numbers Look Like¶

Let’s see what these vectors actually contain (showing just the first 8 dimensions out of 512):

# Token: "The" (position 0)

embedding_The = [ 0.21, 0.15, -0.33, 0.08, -0.12, 0.19, 0.05, -0.28, ...] # Learned

pos_encoding_0 = [ 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 1.00, ...] # Fixed (sin/cos)

final_input_0 = [ 0.21, 1.15, -0.33, 1.08, -0.12, 1.19, 0.05, 0.72, ...] # Sum

# Token: "quick" (position 1)

embedding_quick = [-0.18, 0.42, 0.11, -0.25, 0.37, -0.14, 0.22, 0.09, ...] # Learned

pos_encoding_1 = [ 0.84, 0.54, 0.10, 0.99, 0.01, 1.00, 0.00, 1.00, ...] # Fixed (sin/cos)

final_input_1 = [ 0.66, 0.96, 0.21, 0.74, 0.38, 0.86, 0.22, 1.09, ...] # Sum

# Token: "brown" (position 2)

embedding_brown = [ 0.09, -0.31, 0.44, 0.17, -0.08, 0.26, -0.13, 0.35, ...] # Learned

pos_encoding_2 = [ 0.91, -0.42, 0.20, 0.98, 0.02, 1.00, 0.00, 1.00, ...] # Fixed (sin/cos)

final_input_2 = [ 1.00, -0.73, 0.64, 1.15, -0.06, 1.26, -0.13, 1.35, ...] # SumKey observations:

Embeddings have learned values (positive and negative) that capture word meaning

Positional encodings follow the sin/cos pattern (notice the periodic structure)

Final input is simply the element-wise sum of the two

Same word at different positions gets different final vectors (different PE added)

Summary¶

Embeddings map discrete IDs to continuous vectors where distance equals similarity.

Positional Encodings inject a sense of order into a model that otherwise sees everything at once.

Addition: We simply add these two vectors together. The model learns to separate the “meaning” signal from the “position” signal during training.

Related reading¶

Embeddings at Scale Book:

Next Up: L03 – The Attention Mechanism. This is the “Aha!” moment of the entire series. We will build the logic that allows the model to decide which words in a sentence are most relevant to each other.