This tutorial series builds a production-ready anomaly detection system using ResNet embeddings for observability data.

Introduction: Why ResNet for Anomaly Detection?¶

This tutorial explores Residual Networks (ResNet), a breakthrough architecture that enables training of very deep neural networks. While ResNet was originally designed for computer vision, it has emerged as a surprisingly strong baseline for tabular data and embedding models.

Motivation: Tabular Data and Anomaly Detection¶

Recent research has shown that while Transformers (TabTransformer, FT-Transformer) achieve state-of-the-art results on tabular data, ResNet-like architectures provide a simpler, more efficient baseline that often performs comparably well Gorishniy et al. (2021). For applications like:

Anomaly detection in observability data (logs, network traffic, system metrics)

Self-supervised learning on unlabelled data

Creating embeddings for multi-record pattern analysis

ResNet offers several advantages:

Simpler architecture than Transformers (no attention mechanism overhead)

Linear complexity vs. quadratic attention complexity for high-dimensional tabular data (300+ features)

Strong empirical performance on heterogeneous tabular datasets

Efficient embedding extraction for downstream clustering and anomaly detection

The Use Case: OCSF Observability Data¶

Consider an observability scenario where you have:

Unlabelled data: Millions of OCSF (Open Cybersecurity Schema Framework) records

High dimensionality: 300+ fields per record (categorical and numerical)

Multi-record anomalies: Patterns that span sequences of events

No ground truth: Need self-supervised learning

The approach Huang et al. (2020):

Pre-train a ResNet to create embeddings from individual records

Extract fixed-dimensional vectors that capture “normal” system behavior

Detect anomalies as records/sequences that deviate from learned patterns

This tutorial series will build your understanding of ResNet from first principles, then show how to deploy it in production.

Prerequisites¶

Required Background:

Basic neural network concepts (layers, backpropagation, gradient descent)

Basic Python and PyTorch syntax

Recommended (but not required):

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) — This part uses image examples with CNNs, but we include a brief CNN primer before the code

If you’re primarily interested in tabular data, you can skim the image-based sections and focus on Part 2: Adapting ResNet for Tabular Data

New to neural networks? Start with our Neural Networks From Scratch series:

NN01: Edge Detection - Understanding neurons as pattern matchers

NN02: Training from Scratch - Backpropagation and gradient descent

NN03: General Networks - Building flexible architectures

NN04: PyTorch Basics - Transitioning to PyTorch (used in this tutorial)

Paper References¶

Original ResNet: He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S., & Sun, J. (2016). “Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition.” CVPR 2016.

ResNet for Tabular Data: Gorishniy, Y., Rubachev, I., Khrulkov, V., & Babenko, A. (2021). “Revisiting Deep Learning Models for Tabular Data.” NeurIPS 2021.

TabTransformer Comparison: Huang, X., Khetan, A., Cvitkovic, M., & Karnin, Z. (2020). “TabTransformer: Tabular Data Modeling Using Contextual Embeddings.” arXiv preprint.

The Problem ResNet Solves¶

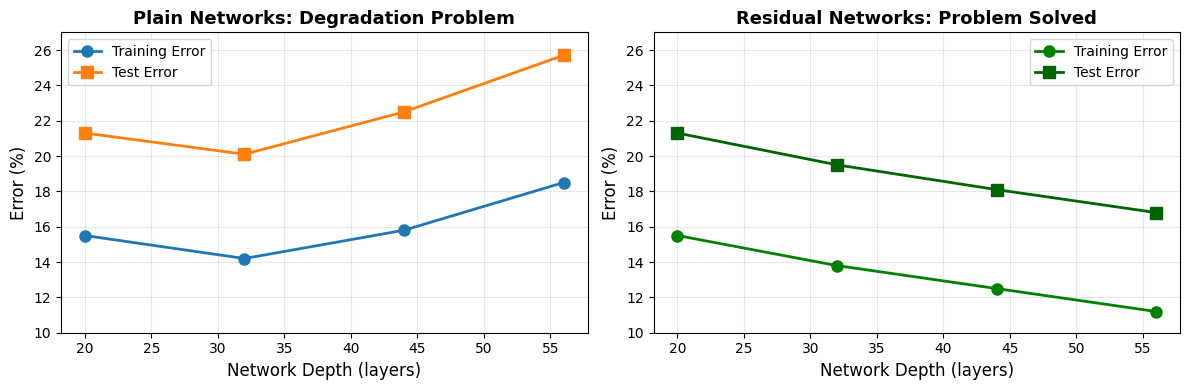

The Degradation Problem¶

Intuitively, deeper neural networks should be more powerful:

More layers → More capacity to learn complex patterns

A 56-layer network should perform at least as well as a 28-layer network (it could just learn identity mappings for the extra layers)

What is an identity mapping? A transformation where the output equals the input: . Think of it like a “do nothing” operation - data passes through unchanged. For example, if a layer receives a vector [1, 2, 3], an identity mapping would output exactly [1, 2, 3]. In theory, deeper networks could use identity mappings in extra layers to match shallower networks, but in practice they fail to learn even this simple operation.

But in practice, this doesn’t happen.

Key Observation: Beyond a certain depth (~20-30 layers), plain networks start to perform worse on both training and test sets. This isn’t overfitting (training error increases too) — it’s optimization difficulty.

Why Plain Networks Fail¶

Two main issues:

Vanishing Gradients: As gradients backpropagate through many layers, they get multiplied by small weight matrices repeatedly, shrinking exponentially. Deep layers learn very slowly or not at all.

Degraded Optimization Landscape: Very deep networks create complex, non-convex loss surfaces that are hard for SGD to navigate. Even though a solution exists (copy the shallower network and make extra layers just pass data through unchanged), the optimizer can’t find it.

What We Need¶

An architecture where:

Deeper is easier to optimize, not harder

Identity mappings are learnable by default

Gradients flow freely to early layers

This is exactly what ResNet provides.

The Core Innovation — Residual Connections¶

The Residual Block¶

The Key Idea:

In a traditional neural network, layers learn to transform input into output directly:

Input → [layers] → Output

The layers must learn the complete transformation from scratch

ResNet changes this by learning the residual (the difference between output and input):

Where:

: Input to the block

: Residual — the learned difference/change to apply (typically 2-3 conv/linear layers)

: Output = Input + Residual change

: The skip connection (also called shortcut connection) — adds input directly to output

Why this helps:

Instead of learning the full transformation from scratch, layers only learn what to change ()

If no change is needed, layers can learn (much easier than learning identity)

The input always flows through unchanged via the skip connection

Visual comparison: The diagrams below show the key architectural difference:

Left (Plain Block): Learns the entire transformation directly from scratch

Right (Residual Block): Only learns the residual to add to the input, where

Why This Works: Intuition¶

Learning Identity is Easy:

If the optimal mapping is identity (output = input, i.e., ), the network just needs to learn

Why? Because , so if , then:

Pushing weights toward zero is much easier than learning the identity function from scratch with many layers

This means “doing nothing” (keeping the input unchanged) is easy to learn

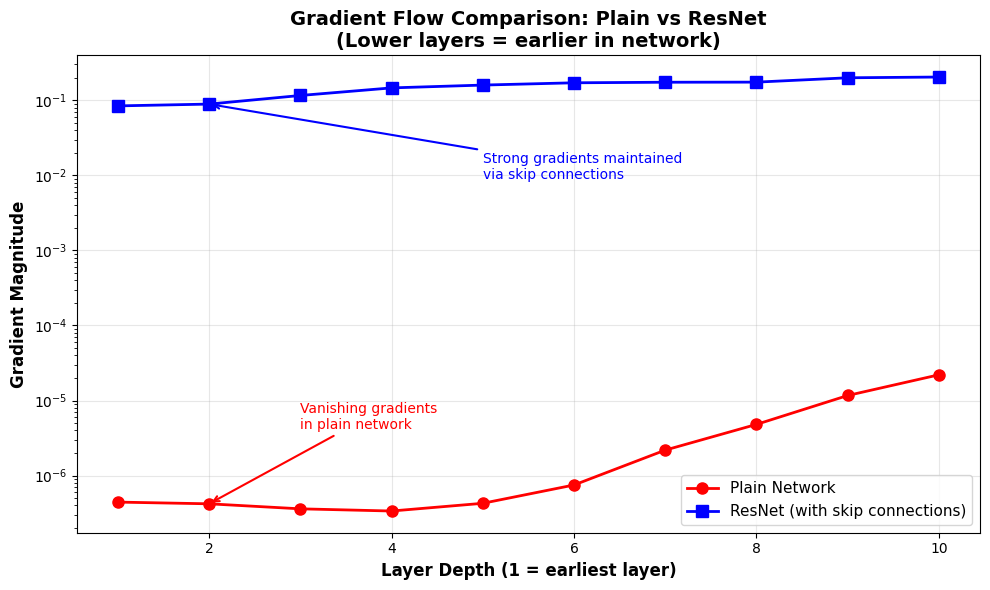

Gradient Flow:

Gradients flow through both paths (main path and skip connection)

Skip connection provides a “gradient highway” directly to earlier layers

Even if has vanishing gradients, passes through unchanged

Source

import logging

import warnings

logging.getLogger("matplotlib.font_manager").setLevel(logging.ERROR)

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

# Simple plain network (no skip connections)

class PlainNetwork(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, num_layers=10):

super().__init__()

self.layers = nn.ModuleList([

nn.Linear(128, 128) for _ in range(num_layers)

])

def forward(self, x):

for layer in self.layers:

x = torch.relu(layer(x))

return x

# Simple residual network (with skip connections)

class ResidualNetwork(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, num_layers=10):

super().__init__()

self.layers = nn.ModuleList([

nn.Linear(128, 128) for _ in range(num_layers)

])

def forward(self, x):

for layer in self.layers:

x = torch.relu(layer(x)) + x # Skip connection!

return x

# Create networks

plain_net = PlainNetwork(num_layers=10)

resnet = ResidualNetwork(num_layers=10)

# Dummy input and target

x = torch.randn(32, 128)

target = torch.randn(32, 128)

# Forward + backward for plain network

plain_output = plain_net(x)

plain_loss = ((plain_output - target) ** 2).mean()

plain_loss.backward()

# Collect gradient magnitudes for each layer

plain_grads = []

for layer in plain_net.layers:

if layer.weight.grad is not None:

plain_grads.append(layer.weight.grad.abs().mean().item())

# Reset and do the same for ResNet

resnet.zero_grad()

resnet_output = resnet(x)

resnet_loss = ((resnet_output - target) ** 2).mean()

resnet_loss.backward()

resnet_grads = []

for layer in resnet.layers:

if layer.weight.grad is not None:

resnet_grads.append(layer.weight.grad.abs().mean().item())

# Plot comparison

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

layers = list(range(1, len(plain_grads) + 1))

ax.plot(layers, plain_grads, 'o-', color='red', linewidth=2,

markersize=8, label='Plain Network')

ax.plot(layers, resnet_grads, 's-', color='blue', linewidth=2,

markersize=8, label='ResNet (with skip connections)')

ax.set_xlabel('Layer Depth (1 = earliest layer)', fontsize=12, fontweight='bold')

ax.set_ylabel('Gradient Magnitude', fontsize=12, fontweight='bold')

ax.set_title('Gradient Flow Comparison: Plain vs ResNet\n(Lower layers = earlier in network)',

fontsize=14, fontweight='bold')

ax.legend(fontsize=11)

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

ax.set_yscale('log') # Log scale to show exponential decay

# Add annotations

ax.annotate('Vanishing gradients\nin plain network',

xy=(2, plain_grads[1]), xytext=(3, plain_grads[1]*10),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle='->', color='red', lw=1.5),

fontsize=10, color='red')

ax.annotate('Strong gradients maintained\nvia skip connections',

xy=(2, resnet_grads[1]), xytext=(5, resnet_grads[1]*0.1),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle='->', color='blue', lw=1.5),

fontsize=10, color='blue')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

print("Observation:")

print(f" Plain Network - Layer 1 gradient: {plain_grads[0]:.6f}")

print(f" Plain Network - Layer 10 gradient: {plain_grads[-1]:.6f}")

print(f" Ratio (layer 10 / layer 1): {plain_grads[-1] / plain_grads[0]:.6f}")

print()

print(f" ResNet - Layer 1 gradient: {resnet_grads[0]:.6f}")

print(f" ResNet - Layer 10 gradient: {resnet_grads[-1]:.6f}")

print(f" Ratio (layer 10 / layer 1): {resnet_grads[-1] / resnet_grads[0]:.6f}")

print()

print("Key insight: ResNet maintains much stronger gradients in early layers,")

print("enabling effective training of deep networks.")

Observation:

Plain Network - Layer 1 gradient: 0.000000

Plain Network - Layer 10 gradient: 0.000022

Ratio (layer 10 / layer 1): 49.664504

ResNet - Layer 1 gradient: 0.084232

ResNet - Layer 10 gradient: 0.204147

Ratio (layer 10 / layer 1): 2.423623

Key insight: ResNet maintains much stronger gradients in early layers,

enabling effective training of deep networks.

What you’re seeing:

Red line (Plain Network): Gradients decay exponentially as you go to earlier layers (left side of plot)

Blue line (ResNet): Gradients remain strong throughout all layers due to skip connections

Log scale: Shows the exponential nature of gradient decay in plain networks

Why this matters for training: Without strong gradients in early layers, those layers barely update during training, making deep plain networks fail to learn effectively. ResNets solve this.

Building Blocks: Basic vs Bottleneck¶

ResNet comes in several standard variants with different depths: ResNet-18, ResNet-34, ResNet-50, ResNet-101, and ResNet-152. The number indicates the total layer count (e.g., ResNet-50 has 50 layers total). These variants use two different types of residual blocks:

Shallower networks (ResNet-18, ResNet-34) use basic blocks with 2 layers each

Deeper networks (ResNet-50, ResNet-101, ResNet-152) use bottleneck blocks with 3 layers each for parameter efficiency

Let’s understand the difference between these two block types.

Basic Block (2 Layers)¶

Used in ResNet-18 and ResNet-34. Simple structure with 2 layers:

Architecture: Input → Layer 1 → Layer 2 → Add skip connection → Output

Skip connection: where is computed through 2 layers

When to use: Shallower networks (18-34 layers) where parameter count isn’t a concern

Bottleneck Block (3 Layers)¶

Used in ResNet-50, ResNet-101, and ResNet-152. Optimized structure using reduce-compute-expand:

Architecture: Input → Reduce → Compute → Expand → Add skip connection → Output

The pattern:

Reduce dimensions (e.g., features) - cheap, small transformation

Compute on reduced dimensions - expensive operations, but on fewer features

Expand back to original size (e.g., features) - cheap, small transformation

Parameter savings: For 256-dimensional features:

Basic block (2 layers): ~589,824 parameters

Bottleneck block (3 layers): ~69,632 parameters (88% reduction!)

When to use: Deeper networks (50+ layers) where parameter efficiency is critical

Why This Works: Intuition¶

The bottleneck design is based on a key insight: most of the useful computation can happen in a lower-dimensional space.

Analogy: Think of data compression. A high-resolution image can be compressed to a smaller size, processed efficiently, then decompressed back. The compressed version still captures the essential information needed for processing.

What’s happening:

Reduce (1×1 conv/linear): Projects high-dimensional features into a compact representation that captures the essential patterns. Like compressing an image before editing it.

Compute (3×3 conv/linear): Performs the expensive transformations on this compact representation. Since we’re working with fewer dimensions (64 instead of 256), this is much cheaper.

Expand (1×1 conv/linear): Projects back to the original high-dimensional space. Like decompressing after processing.

Why it doesn’t hurt performance: The network learns to project into a lower-dimensional subspace where the meaningful transformations happen. The high dimensionality at input/output provides representational capacity, but the actual computation happens efficiently in the bottleneck.

Concrete example (256-dim features):

Basic block: Two 256×256 transformations = 2 × (256² = 65,536) = ~131K params (plus bias/batch norm)

Bottleneck block: 256×64 + 64×64 + 64×256 = 16,384 + 4,096 + 16,384 = ~37K params (88% reduction!)

The bottleneck achieves similar representational power with far fewer parameters by concentrating computation in a lower-dimensional space.

Visual Comparison¶

Basic Block (2 layers):

Bottleneck Block (3 layers):

Diagram explanation:

Both blocks use skip connections (dotted arrows) - the core ResNet innovation

Basic block: Direct 256→256 transformations (more parameters)

Bottleneck block: 256→64→64→256 (fewer parameters - processes in narrow 64-dim space)

ResNet Architecture Overview¶

A full ResNet stacks these blocks into a multi-stage architecture:

Architecture components:

Initial feature extraction: Transform raw input into initial feature representation

Residual stages: Groups of residual blocks, typically 4 stages with increasing feature dimensions (64→128→256→512)

Aggregation: Pool/reduce features to fixed size

Output head: Final layer(s) for the task (classification, embedding, etc.)

Standard architectures:

ResNet-18: [2, 2, 2, 2] basic blocks per stage = 18 layers total

ResNet-34: [3, 4, 6, 3] basic blocks per stage = 34 layers total

ResNet-50: [3, 4, 6, 3] bottleneck blocks per stage = 50 layers total

ResNet-101: [3, 4, 23, 3] bottleneck blocks per stage = 101 layers total

ResNet-152: [3, 8, 36, 3] bottleneck blocks per stage = 152 layers total

Key pattern: Each stage typically:

Increases feature dimensions (64 → 128 → 256 → 512)

Maintains or reduces spatial/record dimensions

Contains multiple residual blocks stacked together

Why this works: The deep stack of residual stages allows the network to learn increasingly abstract representations (from simple patterns to complex concepts), while skip connections ensure gradient flow to all layers.

Summary¶

In this part, you learned the core concepts behind Residual Networks:

The degradation problem: Why plain deep networks fail to train effectively

Residual connections (): The skip connection that solves the problem

Why it works:

Makes learning identity mappings easy ()

Enables gradient flow through skip connections (the “gradient highway”)

Empirically verified with gradient magnitude visualization

Architecture patterns:

Basic blocks (2 layers) for shallower networks (ResNet-18/34)

Bottleneck blocks (3 layers) for deeper networks (ResNet-50+)

Multi-stage design with increasing feature dimensions

Key takeaway: The skip connection is a simple but powerful innovation that makes deep networks trainable. The concept works across all domains—images, text, tabular data—making ResNet one of the most versatile architectures in deep learning.

Next: In Part 2: TabularResNet, you’ll see how to apply these concepts to tabular OCSF data using Linear layers instead of convolutions, plus categorical embeddings for high-cardinality features.

References¶

- Gorishniy, Y., Rubachev, I., Khrulkov, V., & Babenko, A. (2021). Revisiting Deep Learning Models for Tabular Data. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 34, 18932–18943.

- Huang, X., Khetan, A., Cvitkovic, M., & Karnin, Z. (2020). TabTransformer: Tabular Data Modeling Using Contextual Embeddings. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2012.06678.